Securing Data in the Age of AI – Features, Setup, Policies, Licensing & Use Cases

Introduction

Adopting generative AI tools like Microsoft 365 Copilot and ChatGPT brings powerful productivity gains, but also new data security challenges[1]. Organisations need not choose between productivity and protection – Microsoft Purview’s Data Security Posture Management (DSPM) for AI is designed to let businesses embrace AI safely[2]. This solution provides a central dashboard in the Purview compliance portal to secure data for AI applications and proactively monitor AI use across both Microsoft and third-party AI services[2]. In an SMB environment, where IT teams are lean, Purview DSPM for AI offers ready-to-use policies and insights to balance the benefits of AI with robust data governance[1][2].

Overview of DSPM for AI Features

Microsoft Purview’s DSPM for AI builds on existing data protection capabilities (like information protection and DLP) with AI-specific monitoring and controls. Key features include:

Sensitivity Labelling: Integrates with Microsoft Purview Information Protection to classify and label data (e.g. Confidential, Highly Confidential)[1]. Labeled content is respected by AI tools – for example, admins can prevent Copilot from processing documents tagged with certain sensitivity labels[3]. This ensures that AI systems handle data according to its sensitivity level.

Auditing & Activity Logs: Leverages Purview’s unified audit to capture AI-related activities[3]. All interactions with AI (prompts, responses, file accesses by Copilot, etc.) can be logged and reviewed. Auditing is enabled by default in Microsoft 365; once Copilot licenses are assigned, AI interaction events (including prompt and response text) start appearing in the audit logs and DSPM reports[2][3].

Data Classification & Discovery: Automatically discovers and classifies sensitive information across your data estate. DSPM for AI performs real-time data classification of AI interactions[1] – for example, if a user’s Copilot prompt or ChatGPT query contains credit card numbers or customer PII, Purview will detect those sensitive info types. This continuous classification provides insight into what sensitive data is being accessed or shared via AI[1].

Risk Identification & Assessment: Identifies potential data exposure risks (e.g. oversharing or policy violations) related to AI usage. Purview runs a weekly Data Risk Assessment on the top 100 SharePoint sites to flag if sensitive data in those sites might be over-exposed or shared too broadly[2]. It surfaces vulnerabilities – for instance, detecting if a confidential file is open to all employees or if an AI app accessed unusually large volumes of sensitive records[2][1]. These risk insights allow proactive remediation (such as tightening permissions or adding encryption).

Access Permissions Evaluation: DSPM for AI evaluates how AI apps access data and who has access to sensitive information. It correlates sensitivity of data with its access scope to find oversharing – e.g. if an AI is pulling data from a SharePoint site that many users have access to, that could indicate unnecessary exposure[2]. By analyzing permissions and usage patterns, Purview can recommend restricting access or applying labels to secure content that AI is touching.

Proactive Monitoring & Alerts: Real-time monitoring detects when users interact with AI in ways that break policy[1]. Purview DSPM includes one-click, ready-to-use policies that automatically watch for sensitive data in AI prompts and trigger protective actions[2][1]. For example, if an employee tries to paste sensitive text into an AI web app, a DLP policy can immediately warn or block them[3]. This immediate detection and response helps stop data leaks as they happen, not after the fact. Administrators also get alerts and actionable insights on potential incidents (e.g. a spike in AI usage by one user might flag a possible data dump)[1].

Policy Recommendations & One-Click Policies: The DSPM for AI dashboard provides guided recommendations to improve your security posture[2]. It can suggest enabling certain controls or creating policies based on your environment. In fact, Microsoft provides preconfigured “one-click” policies covering common AI scenarios[2]. With a single activation, you can deploy multiple policies – for instance, to detect sensitive info being shared with AI, to block Copilot from processing labeled confidential data, or to monitor risky or unethical AI use[3][3]. These default policies (which can later be tweaked) accelerate the setup of robust protections even for small IT teams.

Compliance and Regulatory Support: Purview DSPM for AI is built with compliance in mind, helping SMBs uphold regulations like GDPR, HIPAA, or Australian Privacy laws even when using AI. It integrates with Microsoft Compliance Manager to map AI activities to regulatory controls[2]. For example, it provides a template checklist for “AI regulations” so you can ensure you have the proper auditing, consent, and data handling measures in place for using AI[2]. It also supports features like retention policies and records management for AI-generated content, and can capture AI interactions for eDiscovery in case of audits or legal needs[3]. In short, it extends your compliance program to cover AI usage, with continuous monitoring and recommendations to maintain compliant data handling and storage practices[2].

These features work together to ensure AI applications adhere to your organisation’s security policies and regulatory standards[1]. With DSPM for AI, an SMB gains visibility into how tools like Copilot, ChatGPT, or Google’s Gemini are accessing and using company data, and the means to prevent misuse or leakage of sensitive information in those AI interactions[1].

Deployment and Configuration in an SMB Environment

Setting up Microsoft Purview DSPM for AI in a small or mid-size business involves enabling the feature, meeting a few prerequisites, and then configuring policies to suit your needs. Below is a step-by-step guide for SMBs to get started and use DSPM for AI effectively.

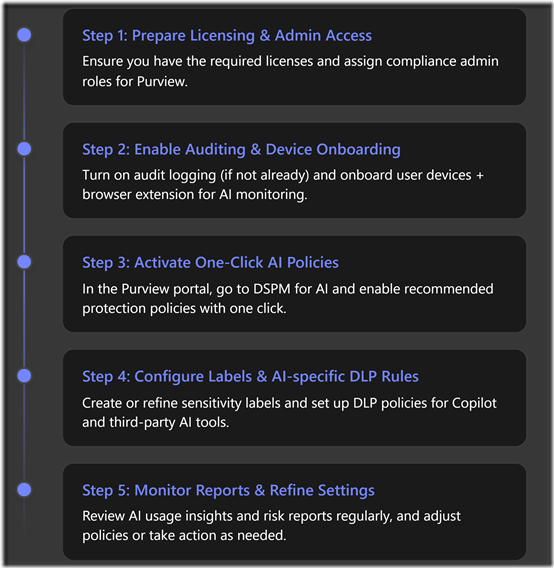

Step-by-Step Setup Instructions

Step 1: Prepare Licensing and Admin Access. First, verify that your Microsoft 365 tenant has the appropriate licenses for the features you plan to use (see Licensing section below for details). At minimum, Business Premium includes core Purview features like sensitivity labels and DLP[4], but advanced AI-specific capabilities (like content capture and insider risk analytics) require the Purview compliance add-on or an E5 licence[5]. Ensure you are assigned a role with compliance management permissions (e.g. Compliance Administrator) in Entra ID (Azure AD), since DSPM for AI is managed from the Purview compliance portal[2].

Next, double-check that Unified Audit Logging is enabled for your organisation. In new Microsoft 365 tenants, auditing is on by default, but it’s worth confirming via the Compliance Center settings[2]. Audit data is crucial because many DSPM for AI insights (like Copilot prompt/response logs) rely on audit events being recorded[3].

Step 2: Enable Auditing (if needed) and Onboard Devices. In the Purview portal (https://compliance.microsoft.com), navigate to Solutions > DSPM for AI[2]. The overview page will list any prerequisites not yet met. If audit is off, turn it on following Microsoft’s instructions (this may take a few hours to take effect)[2].

For monitoring third-party AI websites, you need to set up endpoint monitoring: this means onboarding user devices to Purview and deploying the Purview browser extension. Onboard devices – typically Windows 10/11 PCs – via the Microsoft Purview compliance portal or Microsoft Defender for Endpoint, so that they can report activity to Purview[3]. Onboarded devices allow Purview’s Endpoint DLP to inspect content users might copy to external apps. Then deploy the Purview browser extension (available for Edge and Chrome) to those devices[2]. This extension lets Purview detect when users visit or use known AI web services. It’s required for capturing web activities like someone pasting text into ChatGPT in a browser[3]. On Microsoft Edge, you may also need to set an Edge policy to activate the DLP integration[3]. For example, once devices and the extension are in place, Purview can detect if a user tries to input a credit card number into an AI site and trigger a DLP action[3].

Step 3: Access DSPM for AI and Activate One-Click Policies. With prerequisites done, go to the DSPM for AI page in the Purview portal. Ensure “All AI apps” view is selected to get a comprehensive overview[2]. You’ll see a “Get started” section listing immediate actions. Microsoft provides built-in one-click policies here to jump-start your AI protection[2]. For instance, an “Extend your insights” button will create default policies to collect information on users visiting third-party AI sites and detect if they send sensitive info there[2]. Click through each recommended action – such as enabling AI activity analytics, turning on AI DLP monitoring, etc. – and follow the prompts to activate the corresponding policies.

Behind the scenes, these one-click steps deploy multiple Purview policies across different areas (DLP, Insider Risk Management, Communication Compliance, etc.) pre-configured for AI scenarios[3]. For example, activating “Extend your insights” will create:

- a DLP policy in Audit mode that discovers sensitive content copied to AI web apps (covering all users)[3], and

- an Insider Risk Management policy that logs whenever a user visits an AI site[3].

Similarly, other recommended one-click actions will set up policies like “Detect risky AI usage” (uses Insider Risk to flag users with potentially risky prompts or AI interactions)[3], or “Detect unethical behavior in AI apps” (a Communication Compliance policy that looks at AI prompt/response content for things like sensitive data or code-of-conduct violations)[3]. Each policy is created with safe defaults, usually initially in a monitoring (audit) mode. You can review and fine-tune them later. Allow about 24 hours after enabling for these policies to start gathering data and populating the DSPM for AI dashboards[2].

Step 4: Configure Sensitivity Labels and AI-specific DLP Rules. A crucial part of protecting data in AI is having a data classification scheme in place. If your organisation hasn’t defined sensitivity labels, DSPM for AI can help you create a basic set quickly[2]. Under the recommendations, there may be an option like “Protect your data with sensitivity labels” – selecting this will auto-generate a few default labels (e.g. Public, General, Confidential, Highly Confidential) and publish them to all users, including enabling auto-labeling on documents/email using some standard patterns[2]. You can accept these defaults or customise labels as needed (e.g. creating labels specific to customer data or HR data). Make sure to also configure label policies (to assign labels to users/locations) and consider auto-labeling rules for SharePoint/OneDrive content if you have the capability – auto-labeling requires the advanced Information Protection (available with the Purview add-on/E5)[5]. Even without auto-classification, users can manually apply these labels in Office apps to tag sensitive content.

Next, set up targeted DLP policies for AI scenarios. The one-click setup in Step 3 already created some base DLP policies in audit mode (for monitoring AI usage)[3]. You should now add or adjust preventive DLP rules according to your risk tolerance. Two important examples:

DLP for Copilot: In Purview’s DLP policy section, you can create a policy scoped to the “Microsoft 365 Copilot” location (a new location type)[6]. Configure this policy to detect your highest sensitivity labels or specific sensitive info types, and set the action to “block Copilot” from accessing or outputting that content[3][6]. Microsoft has introduced the ability to block Copilot from processing items (emails, files) that bear certain sensitivity labels[3]. For example, you might specify that anything labeled Highly Confidential or ITAR Restricted is not allowed to be used by Copilot. This means if a user asks Copilot about a document with that label, Copilot will be unable to include that data in its response[3]. (Internally, Copilot will skip or redact such content rather than risk exposing it.) Enabling this type of DLP rule ensures sensitive files or emails stay out of AI-driven summaries.

DLP for Third-Party AI (Web): Create or edit a DLP policy to cover endpoint activities in browsers. Microsoft provides a template via DSPM for AI (the “Fortify your data security” recommendation) that you may have enabled, which includes a policy to block sensitive info from being input into AI web apps via Edge[3]. If not already active, define a new DLP policy with the Endpoint location (which covers Windows 10/11 devices that are onboarded to Purview) and specifically target web traffic (Purview DLP can filter by domain or category of site). You can use Microsoft’s managed list of “AI sites” (which includes popular generative AI services like chat.openai.com, Bard, etc.) as the trigger. The policy condition should look for sensitive info (e.g. built-in sensitive info types like credit card numbers, tax file numbers, health records, or any data classified with your sensitive labels). Set the action to block or block with override. For example, you might block outright if it’s highly sensitive (like >10 customer records), or allow the user to override with justification for lower sensitivity cases. This ensures that if an employee attempts to paste confidential text into, say, ChatGPT, the content will be blocked before leaving the endpoint[3]. In fact, with Adaptive Protection (an E5 feature), the policy can automatically apply stricter controls to high-risk users – e.g. if a user is already flagged as an insider risk, the DLP will outright block the action, whereas a low-risk user might just see a warning[3].

After setting up these policies, use the Purview “Policies” page under DSPM for AI to verify all are enabled and healthy[2]. You can click into each policy (it will take you to the respective solution area in Purview) to adjust scope or rules. For instance, during initial testing you might scope policies to a few pilot users or exclude certain trusted service accounts. Over time, refine the policies: add any custom sensitive info types unique to your business (like project codes or proprietary formulas) and tweak the blocking logic so it’s appropriately strict without hampering legitimate work.

Step 5: Monitor AI Usage Reports and Refine as Needed. Once DSPM for AI is running, the Purview portal will start showing data under the Reports section of DSPM for AI[2]. Allow at least 24 hours for initial data collection. You will then see insightful charts, for example: “Total AI interactions over time” (how often users are engaging with Copilot or other AI apps), “Sensitive interactions per AI app” (e.g. how often sensitive content appears in ChatGPT vs. Copilot), and “Top sensitivity labels in Copilot” (which labels are most commonly involved in Copilot queries)[1][1]. These reports help identify patterns – for instance, if Highly Confidential data is appearing frequently in AI prompts, that might signal users are attempting to use AI with very sensitive info, and you may need to educate them or tighten policies.

Regularly review the Recommendations section on the DSPM for AI dashboard as well[2]. Purview will surface ongoing suggestions. For example, it may suggest running an on-demand data risk assessment across more SharePoint sites if it detects possible oversharing, or recommend enabling an Azure OpenAI integration if you deploy your own AI app. Each recommendation comes with an explanation and often a one-click action to implement it[2]. SMBs should treat these as a guided checklist for continuous improvement.

Also utilize Activity Explorer (within Purview) filtered for AI activities[2]. Here you can see log entries for specific events like “AI website visit”, “AI interaction”, or DLP triggers[3]. For example, if a DLP policy was tripped by a user’s action, you’ll see a “DLP rule match” event with details of what was blocked[3]. You might discover, say, a particular department frequently trying to use a certain AI tool – insight that could inform training or whitelisting a corporate-approved AI solution.

Continuously refine your configuration: if you find too many false positives (blocks on benign content), adjust the DLP rules or train users on proper procedures (e.g. using anonymised data in prompts). If you find gaps – e.g. an AI service not covered by the default list – you can add its URL or integrate it via Microsoft Defender for Cloud Apps (to extend visibility). Purview DSPM for AI is an ongoing program: as your business starts using AI more, periodically update your sensitivity labels taxonomy, expand policies to new AI apps, and leverage compliance manager assessments to ensure you meet any new regulations or internal policies for responsible AI use[2].

Policy Configuration for Microsoft 365 Copilot and Third-Party AI Tools

A core strength of Purview DSPM for AI is that it extends your data protection policies directly into AI scenarios. Here we provide specific guidance on configuring policies for Microsoft 365 Copilot and for external AI applications in an SMB context.

Protecting Data Used by Microsoft 365 Copilot: By design, Copilot abides by Microsoft 365’s existing security framework. It will only access data that the requesting user has permission to access, and it respects sensitivity labels and DLP policies[2][6]. Admins can create explicit policies to control Copilot’s behavior:

Sensitivity Label-based Restrictions: Use Purview DLP to create a rule that targets the Copilot service. In the DLP rule, set a condition like “If content’s sensitivity label is X, then block Copilot from processing it.” Microsoft’s new DLP feature (in Preview mid-2025, GA by Aug 2025) allows detection of sensitivity labels in content that Copilot might use[6]. When such a label is found, Copilot is automatically denied access to that item[6]. For example, if an email is labeled Privileged (using a sensitivity label), a DLP policy can ensure that Copilot will not read or include that email in response to a prompt[6]. This configuration is done in the Purview Compliance Portal under Data Loss Prevention by choosing ‘Microsoft 365 Copilot’ as a policy location and specifying the sensitive labels or data types to act on[6]. Notably, Microsoft has made it such that you don’t need a Copilot license to set up these protective policies – any organization can create Copilot-targeted DLP rules to prepare in advance[6] (though of course Copilot will only be active if you have purchased it).

Data Type-based Restrictions: In addition to labels, consider using sensitive info types. For instance, you might want to prevent Copilot from ever revealing personally identifiable information (PII) like tax file numbers or health record numbers. You can configure a DLP policy: If Copilot’s output would include data matching ‘Australian Tax File Number’ or ‘AU Driver’s License Number’, then block it. This is essentially treating Copilot as another channel (like email or Teams) where DLP rules apply. In practice, Copilot won’t include that content in its responses if blocked – the user might see a message that some content was excluded due to policy.

Retention/Exposure Controls: Leverage Purview’s Retention and Records policies for Copilot interactions if needed. For example, if your industry regulation requires that certain data not be maintained, you can set a retention label to auto-delete Copilot chat content after X days. Also, if using Security Copilot or Copilot in Fabric, enabling the recommended Purview collection policy captures their prompts and responses for compliance auditing[3].

After configuring these, test Copilot’s behavior: e.g., label a document as Secret and try asking Copilot about it with a user account. You should find Copilot refuses or gives a generic answer if policies are correctly in place. Over time, review Copilot-related DLP events in Purview reports to see if it attempted to access something blocked – this indicates your policies are actively protecting data.

Policies for Third-Party AI Tools (e.g. ChatGPT, Bard, etc.): Third-party AI apps are outside the Microsoft 365 ecosystem, so policies focus on monitoring and preventing sensitive data from leaving your environment:

Endpoint DLP for AI Websites: As discussed in the setup, configure Endpoint DLP rules to cover major AI sites. Microsoft Purview comes with a built-in list of “supported AI sites”[2] (this includes OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google Bard, Claude, Microsoft Bing Chat, etc.). You can use this list in your DLP conditions so that the rule triggers when any of those sites are detected. The policy can be in block mode or user override mode. For SMBs, a common approach is to warn/justify – i.e. when an employee tries to paste corporate data into ChatGPT, show a warning: “This action may expose sensitive data. Are you sure?” The user can then either cancel or proceed with justification, and the event is logged[3]. High-risk or highly sensitive cases should be outright blocked and logged. Purview’s one-click “Block sensitive info from AI apps in Edge” policy uses exactly this approach, targeting a set of common sensitive info types (financial info, IDs, etc.) and blocking those from being submitted to AI web apps via Edge[3]. You can customize the sensitive info types and message per your needs. For example, you might add keywords unique to your company (like project codenames) to the policy to ensure those cannot be shared with external AI.

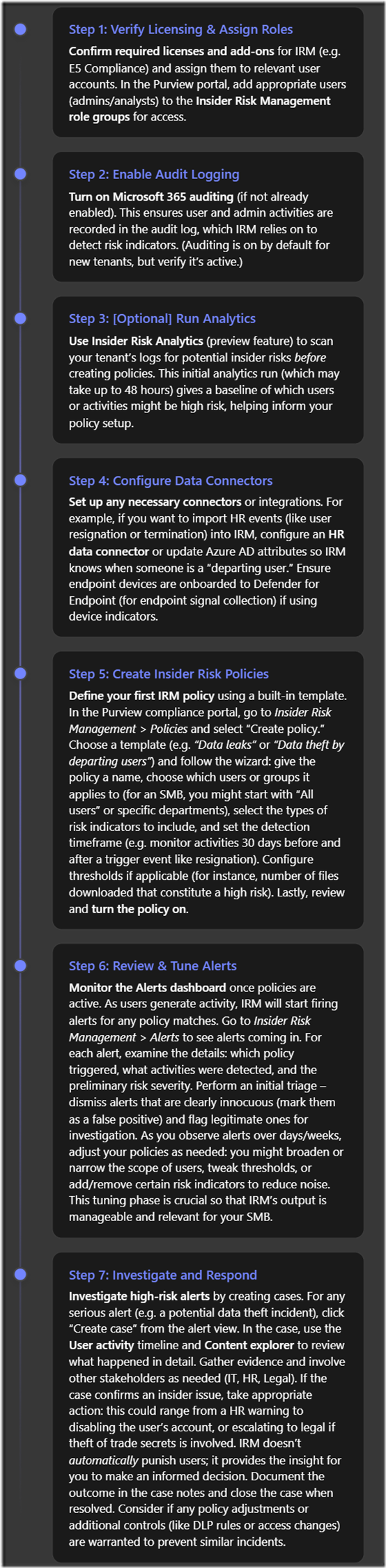

Insider Risk Management (IRM): For an SMB with an E5 Compliance/Purview add-on, Insider Risk Management policies can complement DLP. An IRM policy can watch for patterns that suggest risky behavior, even if individual DLP rules weren’t violated. For AI, Microsoft provides a template “Detect risky AI usage” – this looks at prompt and response content from Copilot and other AI and if a user is frequently attempting to input or extract large amounts of sensitive data, it raises their risk level[3]. It essentially correlates multiple AI interactions over time. If an employee starts copy-pasting client lists into various AI tools, IRM might flag that user for a potential data leakage risk, prompting further investigation or mitigation (like removing their access to certain data). While setting up IRM can be complex (requires defining risk indicators, etc.), the preset AI-focused policy simplifies it for you. SMBs should consider enabling it if they have the license, as it provides an additional safety net beyond point-in-time DLP rules.

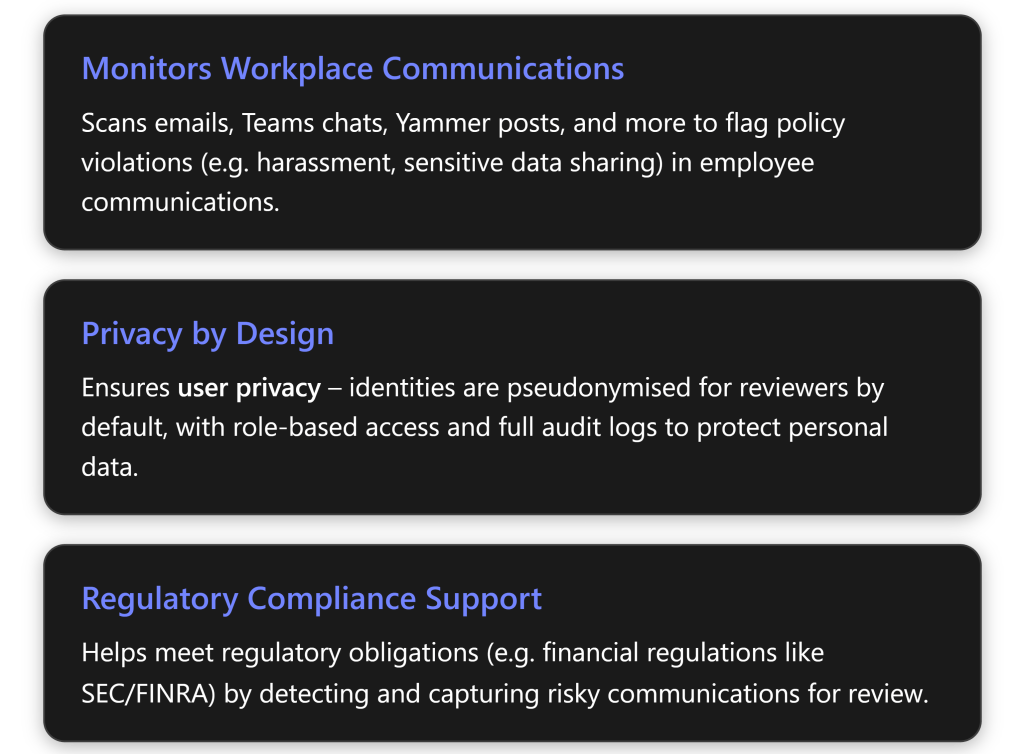

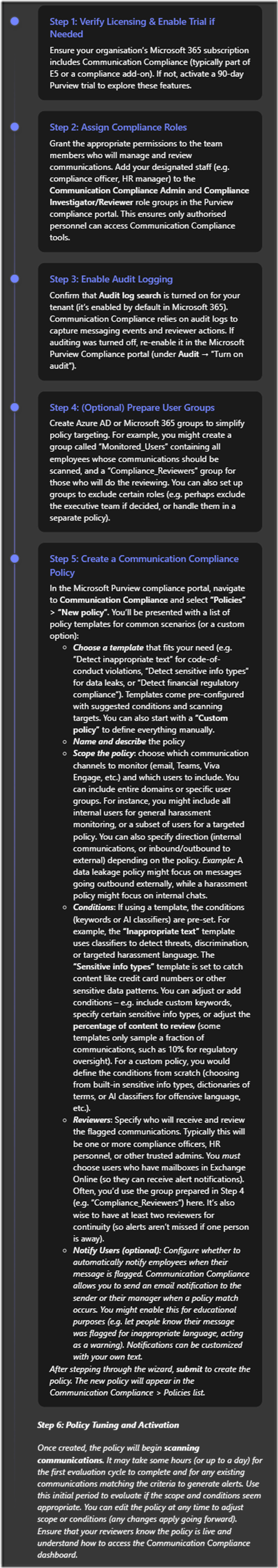

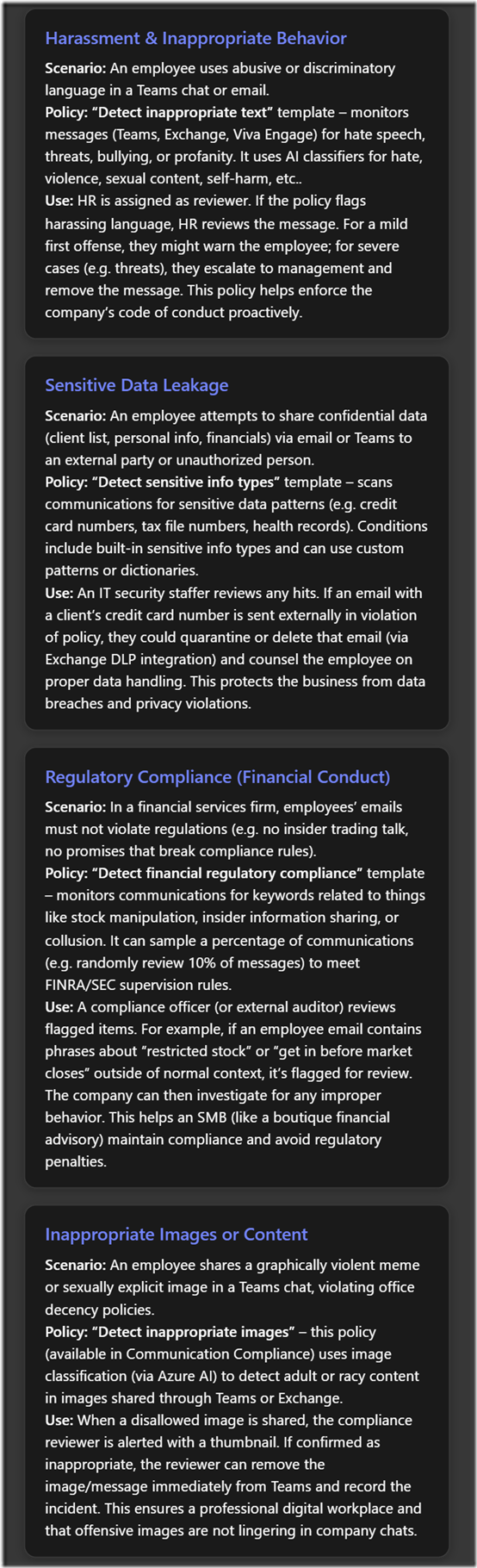

Communication Compliance: Another advanced feature (in E5/Purview suite) is Communication Compliance, which can now analyze AI-generated content. For instance, a policy can detect if employees use inappropriate or regulated content in AI prompts or outputs[3]. Microsoft’s default “Unethical behavior in AI apps” policy looks for sensitive info in prompts/responses, which can catch things like attempts to misuse AI for illicit activities or to share confidential data inappropriately[3]. In an SMB, this could be used to ensure employees aren’t, say, asking an AI to generate harassing language or to divulge another department’s secrets. While not directly a data protection in the sense of preventing data loss, it does enforce broader usage policies and can be part of a responsible AI governance approach.

Cloud App Security (optional): If your organisation uses Microsoft Defender for Cloud Apps (formerly MCAS), you can leverage its Shadow IT discovery and app control features alongside Purview. Defender for Cloud Apps can identify usage of various AI SaaS applications in your environment (by analyzing log traffic from firewalls/proxies or directly via API if using sanctioned apps). You could combine this with Purview DLP by using Cloud Apps’ capability to route session traffic through a conditional access app control, enabling real-time monitoring of what users upload to AI web apps. This is more of an advanced setup, but the Purview DSPM dashboard might highlight to you which AI apps are most accessed by your users[1], helping you focus your Cloud App Control policies accordingly.

In summary, for Microsoft 365 Copilot, focus on label-based and content-based DLP policies and let Copilot’s compliance integration handle the rest. For third-party AI tools, rely on Endpoint DLP to police what data leaves your endpoints, and consider Insider Risk and Communication Compliance for broader oversight. Microsoft has provided templates for all these – by reviewing the pre-created DSPM for AI policies in your portal, you can see concrete examples of configurations for each scenario and adjust them to fit your organisational policies[3][3].

Licensing and Pricing Considerations

Implementing Purview DSPM for AI touches on several Microsoft 365 services, so it’s important to understand licensing. Small and mid-sized businesses often use Microsoft 365 Business Premium, and Microsoft now offers add-ons to bring advanced Purview capabilities to that tier without requiring full Enterprise E5 licenses. Below we compare what features different licenses provide and the respective costs (prices are per user, per month, in Australian dollars):

| License | Included Purview Data Security Features | Cost (approx. AUD) |

|---|---|---|

| Business Premium (Base) | Includes core compliance features: Microsoft Purview Information Protection **P1** (manual sensitivity labeling & encryption), Purview **Data Loss Prevention** for Exchange, SharePoint, OneDrive, Teams (i.e. cloud DLP)[4](https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/1124589/does-microsoft-purview-dlp-comes-with-microsoft-36), basic data retention policies, and **Audit log** (90-day default). Does not include advanced capabilities like auto-labeling, Insider Risk, Communication Compliance, or Endpoint DLP[4](https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/1124589/does-microsoft-purview-dlp-comes-with-microsoft-36). | ~AU$30.20**** |

| Business Premium + Purview Suite Add-on | Adds the full Microsoft Purview compliance suite (equivalent to M365 E5 Compliance): Information Protection & DLP P2 (auto-classification, trainable classifiers, and Endpoint DLP for devices)[4](https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/1124589/does-microsoft-purview-dlp-comes-with-microsoft-36)%5B4%5D(https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/1124589/does-microsoft-purview-dlp-comes-with-microsoft-36), Insider Risk Management (risk scoring, detection of risky actions)[5](https://oryon.net/blog/microsoft-365-business-premium-addons/), Communication Compliance (monitoring of communications for policy violations)[5](https://oryon.net/blog/microsoft-365-business-premium-addons/), Records Management & Archiving (advanced data lifecycle management), eDiscovery (Premium) & Audit (Premium) (1-year audit retention and audit analysis)[5](https://oryon.net/blog/microsoft-365-business-premium-addons/), as well as the **DSPM for AI** dashboard and one-click AI policies[5](https://oryon.net/blog/microsoft-365-business-premium-addons/). Essentially all the Purview features that Microsoft offers in an E5 plan are enabled for Business Premium via this add-on. | ~AU$15.00 (add-on price)[5](https://oryon.net/blog/microsoft-365-business-premium-addons/) |

| Microsoft 365 E3 | Covers the enterprise basics similar to Business Premium: Purview Information Protection P1 and standard DLP (cloud), retention, basic Audit (90 days), Core eDiscovery. Does **not** include Insider Risk or advanced analytics. M365 E3 is roughly analogous to Business Premium in compliance features; the main differences are in device management and security (E3 lacks some features Business Premium has, and vice versa). | ~AU$50–55** (est.) |

| Microsoft 365 E5 | Includes the full range of Purview compliance & security features. For data protection, that means Information Protection P2, Auto-labeling, **Endpoint DLP**, Insider Risk, Communication Compliance, Advanced eDiscovery, long-term audit, Compliance Manager, and DSPM for AI – all **built-in**. No add-ons needed (E5 covers both what the Defender and Purview suites offer)[7](https://diamondit.com.au/microsoft-security-addons/). M365 E5 effectively gives the same capabilities an SMB would get by combining Business Premium + the Defender and Purview add-ons[7](https://diamondit.com.au/microsoft-security-addons/). | ~AU$85–90** (est.) |

Pricing Notes: Microsoft 365 Business Premium has a list price around A$30.20 per user/month in Australia (excluding GST). The newly introduced Purview Suite add-on for Business Premium is priced at US$10, which is roughly AU$15 per user/month[5]. (Similarly, a Defender security add-on is US$10 ~AU$15, or both bundled for US$15 ~AU$22.50.) These add-ons are available as of September 2025 and can be applied to up to 300 users (the Business Premium tenant limit)[5][5]. By comparison, an M365 E5 license that natively includes all Purview features costs about US$57 (~AU$88) per user/month, so for many SMBs it’s far more economical to keep Business Premium and add Purview rather than jumping to E5. In fact, Microsoft quotes that the combined Defender+Purview add-on (at ~$22 AUD) provides roughly a 68% cost saving versus buying equivalent E5 licenses or individual products[8][8].

Feature Availability by License: In practical terms, if you have Business Premium without add-ons, you can still use Purview DSPM for AI in a limited capacity. You will be able to see the DSPM for AI page and get some insights (since you do have basic DLP and labeling). For example, you can label data and apply DLP to Copilot to restrict labeled content[4][6]. However, certain features will not fully function: the one-click policies that leverage Insider Risk or Communication Compliance won’t do anything without those licenses. You also won’t be able to capture the actual prompt/response content from Copilot or other AI (content capture for eDiscovery requires the collection feature which is part of E5). Essentially, Business Premium gives you foundational protection, but the Purview add-on (or E5) is needed for the “full” DSPM for AI experience – including the fancy dashboards of AI usage and the advanced policies for insider risk and content capture[5][1].

For many SMBs, the sweet spot is Business Premium + Purview Suite add-on. This combination unlocks all the E5 compliance capabilities at a fraction of the cost of an E5 license, while allowing the organisation to stay within the 300-user SMB licensing model. It means your Business Premium users get enterprise-grade tools like auto-labeling (which can automatically label or encrypt documents that Copilot might access), advanced DLP actions on endpoints (to stop data going to unsanctioned AI), and insight into AI usage trends – all integrated in the same Microsoft 365 admin experience[5][5].

(Note: The above prices are approximate and current as of 2025. Australian pricing may vary slightly based on exchange rates and whether billed annually or monthly. GST is typically not included in listed Microsoft prices. Always check with Microsoft or a licensing partner for the latest local pricing.)

Example SMB Use Cases and Benefits

To illustrate how Microsoft Purview DSPM for AI can protect a small/medium business’s data, here are several common use cases and how the features come into play:

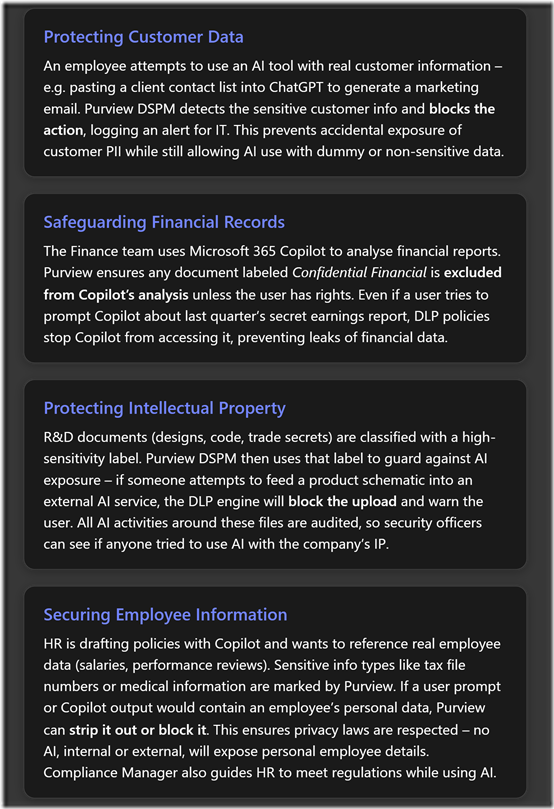

Use Case 1: Protecting Customer Data. Imagine a sales manager tries to use ChatGPT to draft a proposal and copies in a list of customer names and phone numbers. This action could leak personally identifiable information (PII). With Purview DSPM for AI, the moment the manager attempts to paste that data into the ChatGPT site, the Endpoint DLP policy kicks in. For example, it might detect the pattern of phone numbers or customer names marked as sensitive and immediately block the transfer in the browser[3]. A notification would pop up on the manager’s screen explaining that company policy prevents sharing such data with external apps. In the Purview portal, an alert or event log is generated showing that “Sensitive info (Customer List) was blocked from being shared to chat.openai.com”. The manager is thus prevented from inadvertently exposing customer data, fulfilling the company’s privacy commitments. Later, the IT admin sees this event in the DSPM report, and can follow up to ensure the manager uses a safer approach (perhaps using anonymised data with the AI). In essence, Purview acted as a last line of defense to keep customer data in-house[3].

Use Case 2: Safeguarding Financial Records. A mid-sized investment firm (say 50 employees) uses Business Premium and has started deploying Microsoft 365 Copilot to employees. The CFO is using Copilot to get summaries of financial spreadsheets. Purview’s sensitivity labels have been applied to certain highly sensitive financial documents – e.g. the quarterly financial statement is labeled Highly Confidential. When the CFO (or anyone) tries to ask Copilot “Summarize the Q4 Financial Statement,” Copilot checks if it’s allowed to use that document. Thanks to a DLP policy we set (Copilot location blocking that label), Copilot will refuse, perhaps responding with “I’m sorry, I cannot access that content.” The CFO’s request is not fulfilled, which is exactly the intended outcome: that report is too sensitive to feed into any AI. Meanwhile, less sensitive data (like aggregated sales figures labeled “Internal”) might be allowed. Additionally, Purview’s auditing logs record that Copilot attempted to access a labeled item and was blocked[3]. If needed, later on the compliance officer can show auditors that “Even our AI assistants cannot touch certain financial records,” demonstrating strong controls. This scenario shows how DSPM for AI prevents accidental exposure of financial data via AI while still letting Copilot be useful on other data.

Use Case 3: Protecting Intellectual Property (IP). Consider a small engineering firm that has proprietary CAD designs and source code. They classify these files under a label “Trade Secret – No AI”. They also worry about developers using public coding assistants (like GitHub Copilot or ChatGPT) and potentially pasting in chunks of internal code. With Purview, they enable a policy to detect their code patterns (they could even use a custom sensitive info type that matches code syntax or specific project keywords). If a developer tries to feed a snippet of secret code into an AI code assistant in the browser, Purview can intercept that and block it. On the flip side, if the company builds its own secure AI (maybe using Azure OpenAI), they can register it as an “enterprise AI app” in Purview – and Purview DSPM will capture all prompts and outputs from that app for audit[3][3]. That means if any IP is used within that internal AI, it’s still tracked and remains within their controlled environment. Overall, the firm gets to leverage AI for boosting developer productivity on non-secret stuff, while ensuring trade secrets never slip out via AI.

Use Case 4: Securing Employee Information. A human resources team might use Copilot in Microsoft Word to help draft salary review documents or summarise employee feedback. These documents naturally contain highly sensitive personal data. Purview’s role here is twofold: it can automatically classify and label such content (e.g. detect presence of salary figures or personal IDs and apply “Confidential – HR Only” label), and it can enforce policies so that AI cannot misuse it. For instance, an admin can configure that the label “Confidential – HR Only” is in Copilot’s blocked list[3]. So even if an HR staff member tries to use Copilot on a file containing an employee’s medical leave details, Copilot will not process it. Furthermore, if the HR person tries to share any text from that file to an outsider or to a different AI, DLP would intervene. Compliance Manager in Purview also helps here by providing regulatory templates – e.g. if under GDPR, the company should limit automated processing of personal data, the tool will remind the admins of requirements and suggest controls to put in place[2]. Thanks to these measures, the company can confidently use AI internally for HR efficiency while maintaining compliance with privacy laws and keeping employee data safe.

In all these scenarios, Microsoft Purview DSPM for AI acts as a safety harness – it gives SMBs the visibility and control needed to embrace modern AI tools responsibly. By leveraging sensitivity labels, DLP, and intelligent monitoring, even smaller organisations can enforce “our data stays protected, no matter if it’s a person or an AI accessing it.”[1][1] The result is that SMBs can benefit from AI-driven productivity (be it drafting content, analyzing data, or assisting customers) with assurance that confidential information won’t slip through the cracks. Purview DSPM for AI essentially brings enterprise-grade data governance into the AI era, allowing SMBs to innovate with AI securely and in compliance[5][1].

References

[1] Microsoft Purview’s Data Security Posture Management for AI

[2] Learn about Data Security Posture Management (DSPM) for AI

[3] Considerations for deploying Microsoft Purview Data Security Posture …

[4] Does Microsoft Purview DLP comes with Microsoft 365 Business premium?

[5] Microsoft 365 Business Premium: Defender & Purview add-ons

[6] Microsoft Purview DLP to Restrict Microsoft 365 Copilot in Processing …

[7] Stronger Security & Compliance for Microsoft 365 Business Premium

[8] Defender and Purview add-ons for Business Premium | Chorus