When a Microsoft 365 Business Premium subscription is not renewed, the tenant doesn’t shut down instantly. Instead, it transitions through several stages (Expired, Disabled, and Deleted) over a defined timeline. During each stage, different levels of access are available and the status of your data changes. Understanding this lifecycle is crucial for administrators to prevent data loss and plan accordingly[1][1]. This report details each stage step-by-step, who can access the tenant and its data at each point, what happens to user data (including retention and recovery options), and the timelines and best practices associated with each phase. We’ll focus on Microsoft 365 Business Premium (as a representative Microsoft 365 for Business plan), which follows the standard subscription lifecycle for most business plans.

Overview of Post-Expiration Stages

Once a Business Premium subscription reaches its end date without renewal, it goes through three stages before final shutdown[1]:

- Expired (Grace Period) – Immediately after the subscription’s end date, a grace period begins (generally 30 days for most Business subscriptions)[1]. During this stage, services continue to operate normally for end users, and all data remains accessible as usual[1]. This is essentially a buffer period to allow for renewal or data backup before any service disruption occurs.

- Disabled (Suspended Access) – If the subscription is not renewed by the end of the grace period, it moves into the disabled stage (typically lasts 90 days after the grace period)[1]. In this phase, user access is suspended – users can no longer log in to Microsoft 365 services or apps[2]. However, administrators retain access to content and the admin portal, allowing them to retrieve or back up data and to reactivate the subscription if desired[1][1]. The data is still preserved in Microsoft’s data centers during this stage.

- Deleted (Tenant Deletion) – After the disabled period (~120 days after initial expiration, in total), the subscription enters the deleted state[2]. At this final stage, all customer data is permanently erased, and the Microsoft 365 tenant (including its Microsoft Entra ID/Azure AD instance) is removed (if it’s not being used for other services)[1]. At this point, no recovery is possible – the data and services are irretrievable.

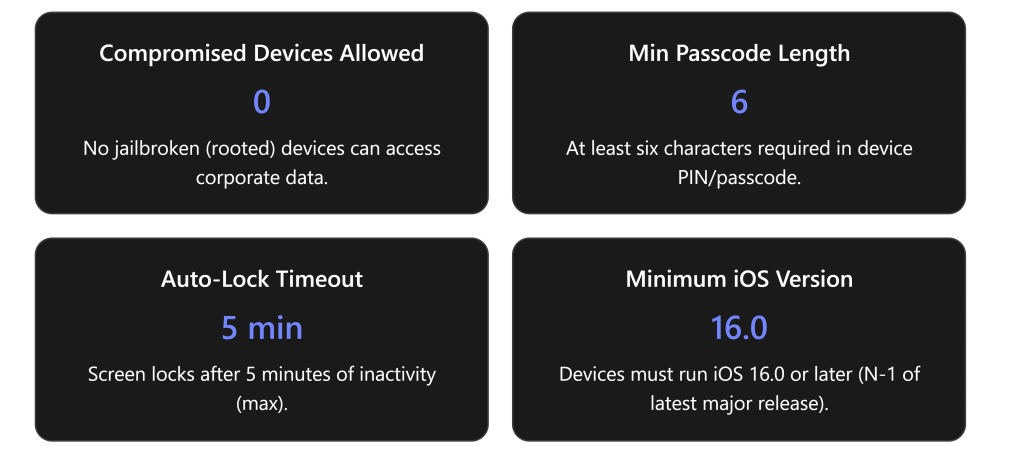

Each stage comes with changes in who can access the tenant’s services and what happens to the stored data. The table below summarizes the key aspects of each stage:

| Aspect | Expired Stage (Grace Period) | Disabled Stage (Suspension) | Deleted Stage (Termination) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | ~30 days after end of term (grace period)[1] | ~90 days after grace period ends[1] | After ~120 days total (post-Disabled)[2] (data is purged) |

| User Access | Full access to all services and data. Users continue to use email, OneDrive, Teams, Office apps, etc., normally.[1] | No user access to Microsoft 365 services. Users are blocked from email, OneDrive, Teams, etc. Office applications enter a read-only “unlicensed” mode[1] (no editing or new content). | No access – user accounts and licenses are terminated. (Users effectively no longer exist in the tenant once deleted.) |

| Admin Access | Admin has full access. Administrators can use the Microsoft 365 admin center and all admin functions normally. They receive expiration warnings and can still renew/reactivate the subscription during this period[1][1]. | Admin access only. Administrators can log in to the admin center and view or export data (e.g. using eDiscovery or content search). However, admins cannot assign new licenses to users while in this state[1]. The admin’s ability to use services might be limited to data retrieval; user-facing apps for admins are also in reduced functionality. | Limited/No admin access to data. Global admins can still sign into the admin portal to manage billing or purchase other subscriptions[1], but all customer data is permanently inaccessible. The subscription cannot be reactivated at this point[1]. If the Azure AD (Entra ID) isn’t used by other services, it is removed along with all user accounts[1]. |

| Data Status | All data retained. Customer data (emails, files, chat history, etc.) remains intact and fully accessible to users and admins[1]. No data deletion occurs in this stage. | Data retained (read-only). All data is still stored in the tenant (Exchange mailboxes, SharePoint/OneDrive files, Teams messages). However, only admins can access this data directly[1] (e.g., an admin could export mailbox contents or files). Users cannot access their data through normal means, but the data has not yet been deleted. | Data deleted. All user and organization data is permanently deleted from Microsoft’s servers[2]. This includes Exchange mailboxes, SharePoint sites, OneDrive files, Teams chat history, Planner data, etc. The data cannot be recovered once this stage is reached. |

| Email & Communications | Email fully functional. Users can send/receive email as normal; mailboxes are active. Teams chats and calls continue normally during this stage. | Email disabled. Exchange Online mailboxes remain in place but are inaccessible to users, and email delivery stops (messages may bounce since the mailbox is now inactive)[2]. Teams functionality is also suspended – users cannot login to Teams, and messages aren’t delivered. (Data in mailboxes and Teams chats is still preserved on the back-end during this time.) | No email/Teams. Mailboxes are gone; inbound emails will not find the recipient (the tenant and users don’t exist). Teams data and channels are removed along with the SharePoint/OneDrive data that stored them. |

| Reactivation Options | Can renew/revive. The subscription can be reactivated instantly by administrators during this entire stage with no loss of data or functionality[1]. (Microsoft continues to accept payment to restore full service during grace.) | Can still renew. Administrators can reactivate the subscription during the 90-day disabled window by paying/renewing[1]. This will restore user access and no data will be lost. If not renewing, admins should use this time to back up any needed data. | Cannot reactivate. Once in Deleted status, it’s too late to simply renew – the subscription is considered terminated. Recovery is not possible; a new subscription would be a fresh start without the old data[1]. |

Note: The timeline above (30 days grace + 90 days disabled) applies to most Microsoft 365 Business subscriptions in most regions[1]. If your subscription was obtained via certain volume licensing programs or a Cloud Solution Provider (CSP), the durations might vary slightly. For example, enterprise volume licensing agreements often have a 90-day grace period and a shorter disabled period, or vice versa[1]. However, for Microsoft 365 Business Premium (direct or CSP purchase), the 30-day grace and 90-day disabled schedule is the standard sequence.

Stage 1: Expired (Grace Period – Full Access Maintained)

When it starts: Immediately after the subscription’s end date, if you did not renew or if auto-renewal was turned off, the subscription enters the Expired status[1]. All previously assigned licenses remain in place during this stage, and the service continues uninterrupted for a limited time.

Duration: Approximately 30 days (for most Business Premium subscriptions)[1] after the license term ends. This 30-day window is often called a grace period.

Access for Users: During the expired stage, end users experience no change in service. All users can still log in and use Microsoft 365 apps and services normally, including Outlook email, Teams, SharePoint, OneDrive, Office applications, etc.[1]. Essentially, full functionality continues as if the subscription were active. Users are typically unaware that the subscription has technically expired – there are no immediate pop-ups or lockouts at this stage beyond possible subtle “license expired” notices in account settings.

Example: If your Business Premium expired yesterday, your employees can still send and receive emails, access their OneDrive files, and use Office apps today without interruption. The experience is unchanged in this grace period.

Access for Admins: Administrators retain full admin capabilities during the expired phase. You can still access the Microsoft 365 Admin Center and all admin portals (Exchange Admin, SharePoint Admin, etc.) normally[1]. In fact, Microsoft will be alerting the admins about the situation: Admins receive notifications in the admin center and via email as the expiration date approaches and passes[1]. These warnings typically inform you that the subscription has expired and remind you to act (renew or backup data) before further consequences.

- Initial Notifications: Prior to expiration, Microsoft sends a series of warnings to the global and billing administrators of the tenant, often starting a few weeks before the due date[1]. For example, admins may get emails at intervals like 30 days, 14 days, 7 days before the subscription ends (exact timing can vary) reminding them to renew. In the Admin Center dashboard, alerts will also indicate the upcoming subscription end. This heads-up is meant to prevent accidental lapses.

- Admin Options during Grace: During the 30-day expired stage, admins have two primary options:

- Renew / Reactivate the Subscription: At any point in the grace period, the admin can renew the subscription (or turn recurring billing back on) to return the status to “Active”[1]. This is a seamless process – once payment is made or the subscription is reactivated, service continues normally without any data loss or further action needed. (If auto-renew was enabled, this happens automatically and the subscription never enters expired status at all.)

- Let it Lapse / Prepare to Exit: If the organization intends not to continue with Microsoft 365, the admin can choose to let the subscription run its course. No immediate action is required to “cancel” at this point because turning off renewal ensures it will expire. During the grace period, it’s wise to begin data backup efforts if you plan to leave the service[3][3]. Microsoft specifically recommends backing up your data during the Expired stage if you are planning not to renew[3][3], since this is a window where everything is still fully accessible. (We will discuss data backup and export options in a later section.)

Data Status: All your data remains intact and fully accessible during Expired status. There is no deletion or removal of any data at this stage. This means:

- Exchange Online mailboxes: All emails, calendars, contacts are retained and functional. Users can continue to send/receive mail normally.

- SharePoint Online sites and OneDrive: All files and SharePoint site content remain unchanged. Users can add, edit, and delete files as usual; synchronization with local devices continues.

- Teams: All chat histories, team channels, and files shared in Teams remain available. Teams meetings can be scheduled and attended normally.

- Other services: Planner tasks, OneNote notebooks, Azure AD user accounts, etc., are all unaffected and continue to operate.

In summary, the Expired stage is a safety net – a 30-day full functionality extension past the subscription end date. It exists to ensure that a lapse in payment or decision doesn’t immediately grind business productivity to a halt, and to give administrators time to evaluate next steps (renew or plan for shutdown)[1][1]. Users have no loss of service in this period, and only admins are aware of the ticking clock via the notifications.

Administrator Tip: Use the grace period wisely. If renewal is intended, it’s best to reactivate before the 30 days are up to avoid any service disruption. If you do not intend to renew, start communicating with users and begin backing up critical data now, while everything is accessible. This might include exporting mailbox PST files, downloading files from OneDrive/SharePoint, and capturing any Teams data you need to retain.

Stage 2: Disabled (Suspended Access – Admin Only)

When it starts: If the subscription is still not renewed once the ~30-day grace period ends, the tenant status automatically changes from Expired to Disabled (sometimes also referred to as the suspended or inactive stage). For most Business Premium subscriptions, this transition happens on Day 31 after expiration (i.e., one month after the subscription’s official end date).

Duration: Typically *90 days in the Disabled state*[1] for standard Microsoft 365 business subscriptions. This 90-day disabled period starts immediately after the grace period. In many scenarios, this means from day 31 through day 120 after your subscription term ended, the tenant is in Disabled status. (Some enterprise agreements might use slightly different timings, but 90 days is the norm for Business Premium.) This 90-day window is critical: it’s the final period during which data is retained and the subscription can be reactivated before permanent deletion.

Access for Users: During the disabled stage, all end-user access is cut off:

- User Login and Apps: Users can no longer log in to Microsoft 365 services (their licenses are now considered “inactive”). If a user tries to sign in to Outlook, Teams, or any Office 365 app, it will fail or indicate that the subscription is inactive. Office desktop apps (like Word, Excel installed via Microsoft 365) will detect the license is expired and **eventually go into a *reduced-functionality mode*[1] – essentially read-only mode. They will start showing *“Unlicensed Product” notifications*, meaning editing and creating new documents is disabled[1].

- Email: Email functionality stops. Users cannot send or receive emails once the tenant is disabled[2]. Exchange Online will stop delivering messages to user mailboxes. External people who send email to your users may receive bounce-back errors (since the system treats the mailboxes as inactive). The emails that already exist in mailboxes remain stored, but users can’t access them.

- OneDrive and SharePoint: Users lose access to their OneDrive and SharePoint content. If they try to access SharePoint sites or OneDrive files via web or sync clients, they will be denied. The data is still present on Microsoft’s servers, but not accessible to the user. Essentially, the SharePoint sites and OneDrive accounts are frozen in place during disabled status.

- Teams: Teams becomes non-functional for users. They cannot log into Teams clients, join meetings, or post messages. Messages sent to them will not be delivered. The Teams data (chat history, channel conversations, etc.) remains stored (since it’s part of Exchange mailboxes and SharePoint) but is inactive.

- Other Services: Any other Microsoft 365 services (Microsoft 365 apps, Power BI if included, Planner, etc.) will be inaccessible to users. For example, OneNote notebooks stored in SharePoint/OneDrive remain but can’t be edited by users. If a user had mobile apps logged in, they would stop syncing or show an error.

In short, regular users are effectively locked out of all Microsoft 365 resources during the Disabled stage. The tenant’s services are in a suspended state, awaiting either reactivation or deletion. For end users, the experience is that everything has stopped working – this is the stage where they will notice the lapse (if they hadn’t during the grace period).

Access for Admins: Administrators still retain access to the system in this stage, though in a more limited capacity:

- Admin Center: Global and Billing Administrators can continue to sign in to the Microsoft 365 Admin Center and view the subscription status[1]. From here, an admin can initiate renewal/reactivation of the subscription if desired (more on that below). Admins can also navigate to the various admin portals (Exchange Admin, SharePoint Admin, etc.). However, their ability to make changes is limited because the subscription is in a suspended state.

- Data Access for Admin: Critically, customer data is still available to admins even though users can’t access it[1]. For example:

- An Exchange Online admin (or a global admin with eDiscovery roles) could use Content Search (eDiscovery) to export mailbox data for a user account. This allows retrieval of emails, contacts, etc., even though the user can’t log in.

- A SharePoint admin can access SharePoint site collections (e.g., via PowerShell or admin interfaces) and could retrieve documents or site data if needed. Additionally, files in OneDrive might be accessible by SharePoint admin because OneDrive is essentially a SharePoint site under the hood.

- If third-party backup solutions were in place, they might still be able to connect via admin credentials to pull data during this stage.

- License Management: One notable restriction is that, in the disabled stage, admins cannot assign or add new licenses to users[1]. The subscription is essentially frozen: you can’t onboard new users under it or extend more licenses. The admin’s role here is mostly to either recover data or restore the subscription, not to operate business-as-usual changes.

Admins do not have normal end-user functionality (for example, if the global admin also had a mailbox on this tenant, they also cannot use email normally for that mailbox, since it’s unlicensed now). But through backend admin tools, they can access content and, importantly, they can still purchase/renew services.

Data Status: The good news in the disabled stage is that all your data is still being retained by Microsoft; nothing has been deleted yet. The data is essentially in stasis:

- Exchange data: All user mailboxes and emails are preserved. Although email flow is halted, the emails and calendar items that were in the mailboxes remain stored on the server. If the subscription is reactivated, users will regain access to their full mailboxes as they were.

- SharePoint/OneDrive data: All site contents and OneDrive files are still present in the SharePoint Online backend. Users are just blocked from viewing/editing them. No files are removed during this stage; storage remains allocated as-is.

- Teams data: Since Teams conversations are stored in user mailboxes (for chat) and SharePoint (for channel files), that data is also intact. Meeting recordings in OneDrive/SharePoint remain as files. Teams channel chats (which are journaled into group mailboxes) remain as well.

- Azure AD (Entra ID): Your Azure AD tenant (which contains user accounts, groups, etc.) is still intact during disabled stage. No accounts are deleted automatically at this point; all user accounts still exist (though they lack active licenses). This is why an admin can still recover data – all the identities and their associated content are present.

- Retention Policies / Legal Hold: If you had any retention or legal hold policies applied to data (for compliance), the data is still there under hold. However, it’s worth noting that these policies do not override the ultimate deletion that will occur if the subscription isn’t renewed by the end of disabled stage. In other words, a legal hold will keep data from user-driven deletion during an active subscription, but once the tenant is shutting down, Microsoft will eventually remove that data after the retention period regardless of hold, because the entire tenant is being decommissioned. We’ll discuss compliance considerations later, but during disabled stage the data on hold is still safe (since nothing is deleted yet).

In summary, Disabled stage = data frozen, users locked out, admins in read-only mode. The business impact here is significant because users can’t work, so this stage is effectively a service suspension. It’s meant to be a final warning period; Microsoft keeps your data around for a bit longer (90 days) in case you realize the mistake or change your mind, but normal operations are halted to incentivize a resolution.

Admin Options during Disabled stage:

- Reactivation: You can still renew or reactivate your Business Premium subscription during the disabled stage[1]. In fact, this is the last chance to do so. Reactivating during this period will immediately restore user access. As soon as you pay for a new subscription term (or otherwise renew), the tenant returns to Active status and all users can use their services again, picking up right where they left off (emails start flowing, files accessible, etc.). No data was lost, so it’s a smooth restoration. From Microsoft’s perspective, this is simply a late payment. In the admin center, a global or billing admin can select the expired subscription and proceed to “Reactivate” or renew[2]; once processed, the status goes back to Active.

- Backup/Data Export: If you do not plan to renew, this 90-day window is your final opportunity to retrieve any remaining data. Admins should use this time to export emails, documents, and other content that the organization needs to retain. For example, export user mailboxes to PST files via eDiscovery, download SharePoint libraries, and save important OneDrive files. After the disabled stage ends, these will be gone forever, so treat this as a countdown to permanent data loss. Microsoft’s guidance is to back up your data while it’s in the Disabled state if you’re canceling the subscription[1].

- No New Data Creation: Obviously, since the services are disabled, you generally won’t be creating new data in this stage via normal use. But be cautious: do not assume Microsoft is backing up your data for you during this time. They are simply retaining it. It’s still the admin’s responsibility to extract and safeguard any information needed.

One more nuance: Microsoft’s policy notes that any customer data left in a canceled subscription might be deleted after 90 days and will be deleted no later than 180 days after cancellation[1]. The standard is 90 days, but they leave room for some systems possibly holding data slightly longer. You should not count on the extra margin beyond 90 days; it’s best to assume 90 days is the deadline, with 180 days being an absolute upper bound in some cases. In practice, for most Business Premium scenarios, at the 91st day of disabled status the tenant moves to deleted status (next stage).

Impact on shared resources: It’s important to note how shared/company-wide data is affected in the disabled stage:

- SharePoint Online sites (like team sites, communication sites) become read-only. Members (users) cannot access them, but an admin could access or export data. If someone from outside (a guest or external sharing link) tries to access content, it will fail because the site is effectively locked along with the tenant.

- Shared mailboxes (if any) and public folders in Exchange are also inaccessible to users. An admin with eDiscovery could export them though.

- Teams shared channels or group chats are inaccessible because no user accounts can sign in.

- OneDrive for Business accounts tied to each user are inaccessible to those users. If an admin needs to, they could use a SharePoint admin take-over of a OneDrive site to retrieve files.

- Applications and Integrations: Any third-party applications integrated via API might stop working if they rely on user credentials or active licenses. If they use app permissions and Graph API, an admin might still retrieve data via API (with app credentials) in disabled stage, since admin consented apps could read data that’s still stored.

User Communication: If you haven’t already, this is the time to let your users know what’s happening. In a planned non-renewal, you likely would have informed users that services would be cut off at a certain date. If the disabled stage comes as a surprise (e.g., an unexpected lapse), you will likely be getting many helpdesk tickets now – “I can’t access email or Teams.” The admin should be prepared to respond (either “we’re working on renewing” or “the service has been suspended and we’re transitioning off of it”).

Stage 3: Deleted (Permanent Deletion of Tenant Data)

When it starts: If no action is taken to renew/reactivate during the 90-day disabled period, the subscription will progress to the Deleted stage. In typical cases, this occurs at or shortly after day 91 of the Disabled stage – which is roughly 120 days (4 months) after the original subscription expiration date. At this point, Microsoft will fully deactivate and remove the tenant.

Duration: The Deleted stage is a terminal state – it’s not a timed phase but rather the end point. The subscription is considered fully terminated and remains in a deleted/non-recoverable state thereafter. (Microsoft does not keep the environment data beyond this in a retrievable way.)

Access for Users: No user access whatsoever. In fact, user accounts themselves are typically purged as part of the tenant deletion (unless your Azure AD is kept alive by another subscription). From the end-user perspective, the Microsoft 365 organization ceases to exist:

- If users try to log in via the Office 365 portal or any apps, their login will fail (the account is gone or the domain is no longer recognized).

- Emails sent to user addresses will bounce with non-delivery reports indicating the recipient was not found, since Exchange Online has removed those mailboxes.

- OneDrive URLs or SharePoint site links will no longer function at all (they’ll likely show an error that the site can’t be found).

- Essentially, by the time of deletion, end users should already have been off the service, as there is nothing to access anymore.

Access for Admins: Administrators have no access to user data once the tenant is deleted. However, there is a small caveat: the admin might still be able to log into the admin portal if the Azure Active Directory is still partially available (for example, if you had other Microsoft services or Azure subscriptions on the same Azure AD, the tenant’s Azure AD might not be deleted). But in terms of the Microsoft 365 subscription:

- The subscription will show as deleted and cannot be reactivated[1].

- Admin Center functionality is minimal: you might only be able to use the admin center to manage other subscriptions or purchase a new one. If your entire tenant was solely for Microsoft 365 and it’s deleted, even the admin portal login might not work anymore once Entra ID (Azure AD) is removed.

- Any attempt to recover data at this stage is fruitless – Microsoft has already begun permanently removing it from their systems.

Data Status: All customer data is permanently deleted once the subscription hits the Deleted stage[2]. This is irreversible data destruction intended to free up storage and maintain compliance with data handling policies (since you’re no longer a customer, they won’t keep your data indefinitely).

Here’s what that means in concrete terms:

- Exchange Online: Mailboxes and their contents are purged from the Exchange databases. The mailbox objects are removed from Exchange Online and the associated data is wiped. Microsoft may retain backups for a short additional buffer (for their own disaster recovery), but not in any way accessible to you. Practically, your emails are gone.

- SharePoint/OneDrive: Site collections for SharePoint and individual OneDrive sites are deleted. The files and list data within them are destroyed. Microsoft might retain fragments or backups for a short time internally, but again, not accessible and eventually wiped as per their data retention disposal policies.

- Teams: Teams data (chat messages, channel content) which lived in Exchange and SharePoint is gone because its underlying storage is gone. Meeting recordings that were in OneDrive/SharePoint are gone. The Teams service itself forgets your tenant.

- Azure Active Directory (Microsoft Entra ID): The Azure AD tenant is deleted (provided it’s not used by any other active subscriptions or services)[1]. This means all user accounts, groups, and other Azure AD objects are removed. If your company had only this one Microsoft 365 subscription in that Azure AD, the directory is now gone. (If you had, say, an Azure subscription or another Microsoft 365 subscription still active on the same directory, the Azure AD remains for that, but the Microsoft 365 service data is still wiped.)

- Backups & Redundancy: Microsoft 365 has geo-redundant backups and such during active subscription, but once the retention period is over, those too are disposed of. By policy, Microsoft will not retain your content beyond the specified period once you’re no longer paying for the service. There is no rollback from the Deleted stage.

In essence, the Deleted stage marks the end-of-life for your tenancy’s data. Think of it as Microsoft performing a complete data deletion and tenant teardown in their cloud.

Recovery Options: At this stage, recovery is not possible through conventional means. Even if you immediately buy a new subscription with the same name or details, it will be a fresh tenant with none of the old data[1]. (Microsoft explicitly notes that if a subscription is deleted, adding a new subscription of the same type does not restore the old data[1].) The only “recovery” would have been to restore from your own backups that you hopefully took during earlier stages. Microsoft Support cannot restore a fully deleted tenant’s content once it’s beyond the retention window.

There is a nuance from the partner-center information: if a partner renewed the same SKU within 90 days after cancellation, sometimes data can be automatically restored[4]. But that is essentially the same as reactivating within the disabled stage. After the ~90 days disabled, those options expire. Post deletion, even if you contact Microsoft, they will apologize that it’s gone.

Impact on shared resources: By now everything is gone:

- SharePoint sites URLs might eventually become available for reuse by other tenants (after a certain period).

- Exchange email addresses might become reusable by others after the domain is removed or reused.

- The custom domain you had on Microsoft 365 (e.g.,

yourcompany.comfor email) is freed up in the Microsoft cloud. (You could take that domain and apply it to a different tenant if you wanted, once the original tenant is deleted or once you deliberately remove it prior to deletion.) - Microsoft Entra ID domain (the onmicrosoft.com domain) is permanently gone.

Final state: The tenant is now closed. Microsoft will have fulfilled any contractual data retention requirements and ensured customer data is wiped. If you attempt to sign in to the account after this, it will behave as if the account does not exist.

Important: If there is any chance you need something from the tenant (a file, an email, anything) after this point, it’s too late. The only recourse would be if you had an offline backup or if perhaps some email was also stored in a user’s Outlook cache or a file was on a user’s local PC. But server-side, Microsoft has cleared it.

Data Retention and Recovery Considerations

Throughout the above stages, a key theme is data retention: Microsoft holds onto your data for a period (grace + disabled) before deletion. Let’s address specific questions about data retention and recovery:

What are the options for data recovery after the grace period?

After the initial 30-day grace (Expired stage) passes, the tenant goes into disabled. During the Disabled stage (days 31–120), you still have two recovery options:

- Reactivate the Subscription: This is the preferred way if you want everything back to normal. As a global or billing admin, you can simply pay for the subscription again (renew for another term) and Microsoft will restore the subscription to active status immediately[1]. All user accounts and data are still there (since they weren’t deleted yet), so this effectively “unpauses” the service.

- Manually Export/Backup Data: If you don’t want to continue the service, the only way to “recover” data for yourself is to manually extract it while the tenant is disabled. That means using admin tools to backup Exchange mailboxes, SharePoint data, etc., to your own storage. Microsoft provides eDiscovery and content search tools that can export data out of Exchange Online and SharePoint Online. Third-party backup solutions (if they were configured earlier) could also be utilized to pull data. But after the grace period, users themselves can’t get their data – it’s on the admin to retrieve it.

Once the disabled period ends and the data is in Deleted status, no recovery method is available via Microsoft. The phrase “subscription can’t be reactivated” at the deleted stage is crucial[1]. Microsoft will have already deleted the data at that point[2].

Is there a final stage before permanent deletion?

Effectively, the Disabled stage is the final stage before deletion. There is no additional “warning stage” beyond disabled; deleted is the point of no return. One could argue that the very end of the disabled period is the last moment. Microsoft does not always send a specific notification right before deletion (you are already warned plenty that the subscription is disabled and needs action). As an admin, you should treat the end of the disabled timeline as the deadline to save anything or renew. Some admins set personal reminders for 90 days after the subscription expired as the last-ditch date.

Can administrators recover data just before it’s permanently deleted?

During the disabled stage (before deletion), yes – admins can recover by reactivating the subscription or by exporting data. Just before deletion, an admin might attempt to call Microsoft Support and request an extension of the disabled period. Occasionally, Microsoft Support might offer a slight grace if you are only a few days past (especially for enterprise accounts). However, this is not guaranteed and not an official policy for Business subscriptions. By policy, once data is deleted, support cannot restore it, as backups are also gone or irretrievable post-180 days. The best practice is to never rely on last-minute support; instead, take proactive steps well in advance of the deletion date.

Are there differences in how different data types are handled?

All data in Microsoft 365 falls under the same overarching lifecycle when a subscription lapses (with the exception of some specialized scenarios like if you have Exchange Online Archiving standalone, etc., which is not the case for Business Premium since it’s a bundle of services). In general:

- Exchange Online (mailboxes) – retained through grace and disabled, then# Lifecycle of a Microsoft 365 Business Premium Tenant After License Non-Renewal

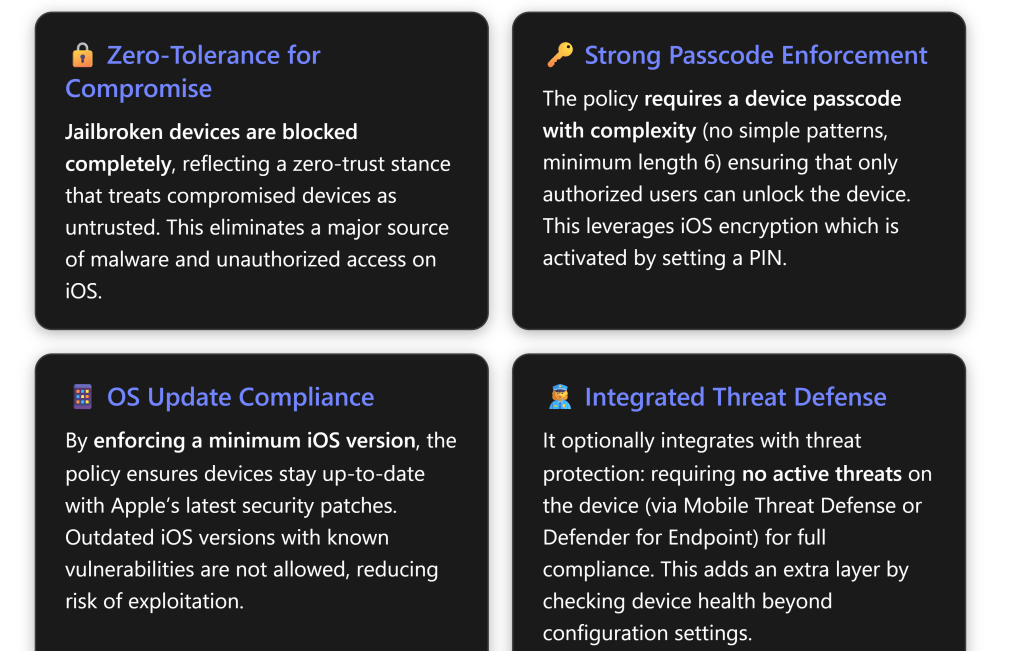

When a Microsoft 365 Business Premium subscription is not renewed at the end of its term, the tenant and its data progress through several lifecycle stages before final termination. Throughout these stages, the level of access for users and admins, as well as the status of stored data, changes in defined ways. This report details each stage – Expired (Grace Period), Disabled (Suspension), and Deleted (Termination) – including who can access services, what happens to data, the timelines involved, and recommended actions for administrators at each phase. We also address special considerations such as user notifications, data recovery options, and compliance (legal holds).

Overview: Stages After a Business Premium Subscription Expires

When a Business Premium subscription ends (e.g. you reach the renewal date without payment or you turn off auto-renewal), the subscription moves through three main stages before the tenant is fully shut down[2][1]:

- Expired (Grace Period) – Immediately after the subscription’s end date, a grace period begins (typically 30 days for direct-purchase business subscriptions)[2][1]. During this stage, services remain fully accessible to users and admins as normal, allowing a last chance to renew or backup data without disruption[1].

- Disabled (Suspended) – If the subscription is not renewed during the grace period, it moves to a disabled state (lasting roughly 90 days for most business subscriptions)[1]. In this stage, user access is turned off – users can no longer use Microsoft 365 services or apps – but administrators still have access to the tenant’s admin portal and data for backup or reactivation purposes[1].

- Deleted (Terminated) – Finally, if no action is taken during the Disabled period, the subscription enters the deleted state (around 120 days after expiration, i.e. after 30+90 days)[2]. At this point all customer data is permanently deleted from Microsoft’s servers and no further recovery is possible[2][1]. The Microsoft Entra ID (Azure AD tenant) is also removed (if it’s not being used by other services)[1].

Each stage brings progressively more restrictions. Table 1 below summarizes the key characteristics of each post-expiry stage in terms of duration, access, and data status:

Table 1: Subscription Lifecycle Stages and Access/Data Status

| Aspect | Expired Stage (Grace Period) | Disabled Stage (Suspension) | Deleted Stage (Termination) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approx. Duration | ~30 days after end-date (typical)[1] | ~90 days after grace period[1] | Begins ~120 days post-expiry (after Disabled)[2] |

| User Access to Services | Fully available. Users have normal access to all Microsoft 365 apps, email, OneDrive, Teams, etc. (no immediate impact)[1][2]. | No user access. Users are blocked from signing in to Microsoft 365 services. Office applications will enter a read-only (“unlicensed”) mode, and users cannot send/receive email or use Teams[1][2]. | No access. The subscription is closed. User accounts and licenses are no longer valid in Microsoft 365; all services are inaccessible and user data is gone[2]. |

| Administrator Access | Full admin access. Admins retain normal access to the admin center and all data. They can manage settings and initiate renewal/reactivation during this period[1]. | Limited admin access. Admins can still sign in to the Microsoft 365 admin center and view or export data. However, they cannot assign licenses to users (since the subscription is suspended)[1][1]. Admins can still purchase or reactivate a subscription during this stage to restore service. | Admin center only (if applicable). After deletion, admins generally lose access to the tenant’s data entirely. The admin portal may only be used to manage other subscriptions or start a new subscription for the organization[1]. If the Azure AD tenant itself is deleted, even admin sign-in is no longer possible. |

| Data State & Retention | Data intact. All customer data (emails, files, SharePoint/OneDrive content, Teams data, etc.) remains fully retained and unchanged in this stage[1]. No data is deleted while in the 30-day grace period. | Data retained (admin-only). All data is still retained in the backend without deletion. Only admins have access to this data during the Disabled stage[1]. For example, SharePoint and OneDrive files remain stored and can be accessed by an admin (or exported via eDiscovery tools), but end-users cannot access them[2]. Exchange mailboxes are preserved, but emails stop flowing to users’ inboxes (messages may queue or bounce)[2]. | **Data **permanently deleted. All customer data stored in the Microsoft 365 tenant is irreversibly purged by Microsoft[2]. This includes Exchange mailboxes, SharePoint sites, OneDrive files, Teams chat history, and any other content. The Azure AD (Entra ID) for the tenant is also deleted (unless it’s linked to other active services)[1]. No data can be recovered once this stage is reached. |

| Reactivation Options | Subscription can be reactivated by admins at any time during this stage. A global or billing administrator can renew or purchase licenses to return the subscription to Active status with no loss of data[1]. | Subscription can still be reactivated during this stage. Admins can pay for the subscription and restore full functionality for users. Once reactivated during the Disabled period, all users regain access and data is again fully accessible[2]. | Cannot be reactivated. After deletion, the subscription and its data cannot be restored by renewing. If you later re-purchase Microsoft 365, it will be a fresh tenant without the old data[1]. |

Table 1: The progression of a lapsed Microsoft 365 Business subscription through Expired, Disabled, and Deleted states, with access permissions and data status at each stage.[1][1]

As shown above, a Business Premium tenant that is not renewed has about 120 days (4 months) from expiration until data is permanently lost, under the typical schedule (30 days Expired + 90 days Disabled)[1]. This timeline can vary slightly based on how the subscription was purchased (for instance, enterprise volume licensing agreements may have different grace periods)[1], but for direct and cloud subscriptions of Business Premium, the 30/90 day pattern holds in most cases.

Below, we detail each stage step-by-step, including the access level for users vs. admins, what happens to data and services, and what actions should be taken during that stage. We also cover the notifications admins receive as the subscription nears expiry and discuss special considerations (like legal compliance holds and data recovery).

Stage 0: Before Expiration – Warnings and Renewal Options

Before diving into the post-expiration stages, it’s important to note what happens leading up to the subscription’s end-date. Admins are not caught by surprise when a Business Premium subscription is about to expire:

- Advance Notifications: Microsoft sends multiple warnings to administrators as the renewal date approaches[1]. These notifications appear in the Microsoft 365 admin center and are sent via email to billing administrators. They typically start some weeks before expiration and increase in frequency as the date nears. (For example, an admin might see reminders a month out, then 1-2 weeks out, and a final reminder a few days before expiry, ensuring they are aware of the pending license lapse.)

- Admin Center Alerts: In the Microsoft 365 Admin Center dashboard, alerts will indicate an upcoming subscription renewal deadline. Global and billing administrators are informed that the Business Premium subscription will expire on a given date if no action is taken.

- End-User Notices: Generally, end-users do not receive expiration notices at this stage. The warnings are directed to admins. Users continue to work normally and will only see impact if the subscription actually lapses. (End-users might eventually see “Your license has expired” messages in Office applications after the grace period, but not before that point[1].)

Administrators have options before expiration:

- Renew or Extend – The admin can renew the subscription (manually or via auto-renewal if enabled) before the expiration date to avoid any service interruption[1]. This could involve confirming payment for the next term or increasing seat counts if needed. If auto-renew was turned off intentionally (perhaps to allow it to lapse), the admin can still re-enable recurring billing prior to expiry to keep the tenant active[1].

- Let it Expire – If the organization decides not to continue with Microsoft 365, the admin can simply let the subscription run its course. Turning off recurring billing ensures it ends on the expiration date and does not charge again[1]. In this case, the stages described below will begin once the term expires. (Microsoft recommends performing data backups of critical information before the subscription ends if you plan not to renew[1].)

Once the expiration date arrives without renewal, the tenant immediately enters the Expired (grace period) stage. The sections below describe each subsequent phase in detail.

Stage 1: Expired (Grace Period – Days 1 to ~30 after Expiry)

Description: The Expired stage is a grace period of approximately 30 days that begins immediately after the subscription’s end date (Day 0 of non-renewal)[1]. During this time, the service is still essentially “up” and running normally. Microsoft provides this grace period to allow organizations a final opportunity to correct a lapsed payment or decide on renewal without cutting off access right away[1].

Duration: For Business Premium (and most Microsoft 365 business plans), the Expired status lasts 30 days from the expiration date[2]. (Some enterprise agreements might have a longer grace by contract, but 30 days is standard for cloud subscriptions[1].)

Access for Users: During the Expired stage, **end users *experience no change* in service[1]. All users can continue to log in and use Microsoft 365 apps and services as if nothing happened:

- Users can send and receive emails via Exchange Online, and their Outlook continues to function normally[2].

- OneDrive and SharePoint Online files remain accessible; users can view, edit, upload, and share documents during this period.

- Teams chat, calls, and meetings continue to work as usual.

- Desktop Office applications (Word, Excel, etc.) remain fully functional – no “unlicensed” warnings yet.

- Any other services included in Business Premium (such as Microsoft Defender for Office 365, Intune, etc.) remain operational during grace.

In short, the grace period means business continuity: your staff likely won’t even realize the subscription has formally expired, provided the admin resolves it before the grace ends.

Access for Admins: Administrators still have full administrative control during the Expired stage:

- Admins can sign in to the Microsoft 365 admin center and use all admin functionalities normally[1].

- Admins can add or remove users, though (since the subscription is technically expired) they should not remove any licenses that are in use – but they can still manage settings and view all data.

- However, no new licenses can be assigned beyond what was already there at expiry[1]. (If an admin tries to assign a license to a new user in an expired subscription, it won’t let them since the plan isn’t active for additional seats.)

- Importantly, admins are the ones who can take action to end the Expired stage: by reactivating the subscription (i.e., processing payment). We cover this under “Actions” below.

Data Status: All customer data remains intact and fully accessible during the Expired stage[1]. Microsoft does not delete or restrict any data at this point, because the assumption is that you may renew and continue using the service. Key points:

- Exchange Online mailboxes: All email messages, contacts, calendars, etc., are retained with no loss. Users can continue to use mail normally. New emails are delivered and nothing is queued or bounced at this stage.

- SharePoint Online sites and OneDrive: All files and site contents remain exactly as they were. Users can add new files or modifications, which are saved normally within the tenant.

- Teams data: Chat history, team channel content, calendars, etc., remain available and continue accumulating normally.

- Azure AD (Entra ID): The directory of user accounts remains fully in place. User accounts are still active and tied to their licenses as before. No accounts are deleted during grace.

No special data retention policy kicks in yet – effectively, the tenant is in a state of full functionality, just with a clock ticking in the background. If the admin renews within this 30-day window, the subscription returns to Active status and everything continues uninterrupted, with no data loss or changes needed[2].

Administrator Notifications and Actions in Expired stage:

- Ongoing Warnings: The admin center will display alerts like “Your subscription has expired – reactivate to avoid suspension” (or similar wording). Microsoft will continue sending emails to admins during the grace period as reminders that the subscription needs attention.

- Reactivation: Admins can reactivate/renew the subscription at any point in the Expired stage by initiating payment (turning the subscription back to Active)[1]. This is typically done in the Billing section of the admin portal by selecting the expired Business Premium subscription and paying the renewal invoice or re-enabling a payment method. Once reactivated, the “Expired” status is lifted immediately – no data or access was lost, and users experience no downtime[2].

- Backup Plans: If the organization decides not to renew (i.e. intends to let the subscription lapse permanently), the Expired stage is a good time to begin data backup and transition efforts. Microsoft specifically recommends backing up your data before it gets deleted if you plan to leave the service[1][1]. During the 30-day grace, since everything is accessible, admins can use content export tools (like the eDiscovery Center to export mailboxes to PST, or SharePoint’s SharePoint Migration Tool or manual download to save libraries) to capture important information. Third-party backup utilities can also be run at this stage to archive data while all accounts are active.

- No Immediate User Impact: Because users have full access, an admin might choose to notify users (internally) that the subscription will not be renewed and advise them to save any personal files from OneDrive if needed. However, from a service perspective, users won’t see any difference during these 30 days.

Summary: The Expired (grace) stage is essentially a safety net period. All functionality is retained for ~30 days after a Business Premium subscription lapses[2]. This stage exists to prevent accidental loss of service due to a missed payment or oversight. Administrators should use this period to either renew the subscription or prepare for the next stage (suspension) by backing up data or informing users, depending on whether the plan is to continue or discontinue the service.

Stage 2: Disabled (Suspension Period – ~Day 31 to Day 120)

If no renewal action is taken during the 30-day grace, the grace period ends and the subscription status automatically changes from Expired to Disabled. This marks the beginning of the service suspension phase, where user access is cut off but data is still held for a limited time.

Description: The Disabled stage is a period of service suspension that lasts for up to 90 days after the end of the grace period[1]. In this stage, the subscription is not active, and thus normal functionality stops for end users. However, the tenant’s data is not yet deleted – Microsoft keeps it in storage for this period, giving a final window for recovery or renewal.

Duration: Approximately 90 days (three months) after the Expired stage. For most Business subscriptions, the Disabled status extends from day 31 through day 120 after subscription expiry[1]. (In total, Expired + Disabled ~ equals 120 days post-expiration. Some Microsoft documents refer to the full 90-day retention here.) In practice, Microsoft assures at least 90 days of Disabled status for data retention; in some cases data might be kept slightly longer (up to 180 days maximum after cancellation, per policy) but 90 days is the standard to count on[1].

Access for Users: During the Disabled stage, end users lose access to all Microsoft 365 services under that subscription:

- User Login and Apps: Users who try to sign in to any Microsoft 365 service (Outlook, Teams, SharePoint, etc.) will no longer be able to authenticate under this tenant’s credentials, because their licenses are now in a suspended state. Essentially, the licenses are not valid during Disabled status, so users are blocked from using cloud services.

- Office Applications: If users have the Office desktop apps installed (via their Business Premium license), those apps will detect the subscription is expired/disabled. They will eventually go into “reduced functionality mode,” which means view-only or read-only access. In Office, a banner may appear saying “Unlicensed Product”[1]. Users can still open and read documents, but editing or creating new documents is disabled while the product is unlicensed.

- Exchange Email: Email services become inactive. Users will not be able to send or receive emails with their Exchange Online accounts once disabled. If someone emails a user, the message may not be delivered (likely the sender will receive a bounce/backscatter indicating the mailbox is unavailable). The user cannot log into Outlook or OWA at this stage. The email data (existing mailbox contents) still exists on the server, but it’s inaccessible to the user and essentially “frozen” in place until potential reactivation.

- SharePoint and OneDrive: Users cannot access SharePoint sites or their OneDrive files via the usual interfaces. If they attempt to visit SharePoint or OneDrive links, they will likely get an access denied or a notice that the account is inactive. In effect, SharePoint Online sites and OneDrive accounts are inaccessible to the users, though the content still exists in the backend.

- Teams: Microsoft Teams functionality is also disabled for users. They cannot log into Teams app or join meetings with their M365 account. Messages sent to them in Teams chats during this period will not reach them (the account is inactive). Any scheduled meetings created by that user might fail or appear orphaned.

- Other Services: Any service that required an active user license (e.g., Microsoft Intune device management, or Office mobile apps tied to account) will not be usable by the user during the Disabled stage.

In summary, from the user perspective the account is effectively “locked out”. They have no access to emails, files, or any Office 365 app. It’s as if their license was removed entirely. This typically causes immediate impact in the organization – for example, employees will notice they can’t log in one morning, which likely prompts urgent action if it was unintentional.

Access for Admins: Even though end users are locked out, administrators still have limited access to the environment during the Disabled stage:

- Admin Center Access: Global and Billing Admins can continue to log in to the Microsoft 365 Admin Center and view the tenant’s settings[1]. The Admin Center will clearly indicate the subscription is disabled due to non-payment. Admins can navigate the interface to gather information or perform certain tasks (with some restrictions).

- Data Access for Admins: Crucially, admins can still access or extract data during this stage, even though users cannot. The Microsoft documentation states “data is accessible to admins only” in the Disabled state[1]. This means:

- An admin can use content search/eDiscovery tools to open mailbox content and export emails. For instance, a compliance admin could search the user’s mailbox and export items to a PST file. (Admins might not be able to simply log in to the user’s mailbox via Outlook, since the user license is off, but using admin tools or converting the mailbox to a shared mailbox temporarily could allow access. Additionally, third-party backup tools with admin credentials can retrieve the data.)

- For SharePoint/OneDrive, a SharePoint administrator can likely still access SharePoint Online Admin Center and use features like the SharePoint Management Shell or OneDrive admin retention tools to recover files. Also, files might be accessible if the admin assigns themselves as site collection admin to the user’s OneDrive site and then downloads content.

- Any data in Microsoft Teams (which actually stores channel files in SharePoint and chat in Exchange mailboxes) can be retrieved via those underlying storage mechanisms if needed by an admin.

- License Management: In the admin portal, the subscription will show as disabled. Admins cannot assign any of the Business Premium licenses to users during this period[1] (the system won’t allow changes because the subscription isn’t active). The admin also cannot add new users with that license. Essentially, capacity to manage user licensing is frozen.

- Other Admin Functions: Admins can still perform tasks not related to that subscription’s licenses. For example, if the tenant had other active subscriptions (like perhaps Azure services or a different M365 subscription), they can still manage those. They can also manage domain settings, view reports, or use the admin center for things that don’t require modifying the disabled subscription.

It’s important to note that while admins have access to data, this doesn’t mean they can use the services in a traditional sense. For example, an admin’s own mailbox (if their user account was also under the now-disabled subscription) would also be inaccessible via normal means. The admin may need to use specialized admin tools to extract their own mailbox data too. The admin advantage is that they can go into the backend and get data, not that they can fully use the apps.

Data Status: All customer data remains preserved during the Disabled stage; however, it is in a read-only, dormant state:

- No Data Deletion Yet: Microsoft does not delete anything during the Disabled period. Your users’ emails, files, and other content are all still stored safely in the cloud. The difference is just that users can’t reach it. Think of it as the data being in a vault that only admins can unlock at this point.

- OneDrive/SharePoint Content: All documents and sites remain in place. If an admin were to reactive the subscription, users would find their OneDrive and SharePoint files exactly as they left them. If the organization is not renewing, admins should take this time to extract any files needed. For example, the admin could manually access each user’s OneDrive (with admin privileges) and copy data to a local storage or alternate account. Similarly, SharePoint sites can have their contents exported (via SharePoint Migration Tool or via saving libraries to disk).

- Exchange Online Mailboxes: Mailboxes remain stored with all their email and calendar content. New incoming emails during Disabled stage may not be delivered to these mailboxes (senders might get an NDR message after a certain time). However, the content up to the point of entering Disabled stage is still there. Admins can use eDiscovery or content search to get the mailbox data. If the plan is to migrate away from M365, this stage is the time to export user mailboxes to PST files or another mail system. (If a mailbox was placed on Litigation Hold or had a retention policy, its data is still preserved here as well – more on compliance later.)

- Teams Data: Teams chats and channel messages from before the Disabled stage remain stored (in user mailboxes or group mailboxes for channels). While users can’t use Teams now, an admin could retrieve chat content via Compliance Content Search if needed. Files shared in Teams are either in SharePoint (still accessible to admin) or OneDrive (accessible via admin).

- Public Folders / Other Services: If any other data (like public folders in Exchange, or Planner tasks, etc.) existed, they also remain intact in the backend but inaccessible to users.

In essence, the Disabled period is your “last chance” to either restore service or save your data. Microsoft has put a hold on deleting anything, but the clock is ticking.

Administrator Options and Actions in Disabled stage:

- Reactivating the Subscription: The most straightforward way to exit the Disabled stage is to reactivate the subscription by renewing payment within this 90-day window[1]. The global admin or billing admin can go into the Admin Center’s billing section and pay for the Business Premium subscription (or purchase a new subscription of equal or greater value and assign licenses to users). Once the payment is processed and the subscription returns to Active, all user access is restored immediately. Users will be able to log in again, emails will resume delivery, and the “unlicensed” notices on Office apps will disappear. Essentially, it will be as if the lapse never happened – no data was lost and everything resumes from where it left off[2]. This is the ideal outcome if the lapse was unintended or circumstances changed to allow renewal.

- Note: Reactivating after a lapse may require paying for the period that was missed or starting a new term. Microsoft allows reactivation in-place during Disabled stage, so you generally keep the same tenant and just resume billing going forward.

- Backing Up Data: If the decision is to not renew at all, the Disabled stage is the final opportunity to back up any remaining data from the Microsoft 365 tenant:

- Admins should ensure they have exported all user mailboxes (using eDiscovery PST export, or a third-party backup tool). As a best practice, do this early in the Disabled phase rather than waiting till the last minute, to avoid any accidental data loss or issues.

- All SharePoint sites and OneDrives that contain needed files should be backed up (download documents, or use a script to fetch all files).

- If specialized data exists (like Project data, forms, or Power BI content), those should also be retrieved via available export options.

- Microsoft’s notice is that any customer data left after the Disabled period “might be deleted after 90 days and will be deleted no later than 180 days” following the subscription cancellation[1]. So administrators should act under the assumption that once the standard 90 days are up, data could be purged at any time. Waiting beyond this point is extremely risky.

- User Communication: If not renewing, it’s likely users are already aware (since they lost access). Admins should communicate with users that the service has been suspended. If the org is transitioning to another platform (like a different email system), this is when users need instructions on how to proceed (for example, accessing a new email account elsewhere). If the loss of service was unintentional, admins would by now be working to get it reactivated – and users should be informed that IT is addressing the downtime.

- Grace in Disabled? It’s worth noting that while we say ~90 days, admins should not rely on any extra hidden grace beyond that. Microsoft’s policy is clear that data will be deleted after the Disabled period, and sometimes they cite 90 days explicitly, other times “no later than 180 days” to cover edge cases[1]. The safest interpretation: assume 90 days exactly. In many cases, tenants have reported data still being there up to 120 or even 150 days after expiration, but this is not guaranteed. The only guarantee is within 90 days.

In summary, the Disabled stage means the tenant is effectively offline for users but the data is frozen in place. Administrators can either renew the subscription to immediately restore functionality or finalize their data extraction and migration plans. If neither is done by the end of this stage, the tenant will move to the final stage and data will be permanently lost. This stage is critical for admins to manage carefully: it is the last buffer preventing permanent data loss.

Stage 3: Deleted (Final Tenant Deletion – After ~120 Days)

The final stage in the lifecycle is the Deleted stage, which the subscription enters after the Disabled period runs its course with no reactivation. Once this stage is reached, the subscription and all associated data are considered fully terminated by Microsoft.

Description: The Deleted stage represents the point at which Microsoft 365 has permanently turned off the subscription and purged customer data. In other words, the tenant is deprovisioned from Microsoft’s services. This typically happens automatically at the end of the 90-day Disabled window (for Business Premium, roughly 120 days after the initial expiration, as depicted in the timeline)[2].

Duration: Deleted is a terminal state, not a time-limited stage. Once in the Deleted status, the subscription doesn’t transition further – the tenant remains off. At this point the subscription is considered “non-recoverable”[4]. There is no additional grace; the data is gone and the service will not come back unless starting from scratch.

Access for Users: There is no user access at all in the Deleted stage:

- All user accounts from the former tenant no longer have any Microsoft 365 service tied to them. In fact, if the Azure Active Directory (Entra ID) for the tenant is deleted (as it typically is if no other services were using it), the user accounts themselves are deleted too[1].

- If a user tries to log in, their account won’t be found. Their email addresses are no longer recognized by Microsoft 365. Essentially, from the cloud service perspective, those users do not exist anymore in that context.

- Any attempt to access data (SharePoint sites, OneDrive URLs, etc.) will fail because those resources are no longer available in Microsoft’s cloud.

Access for Admins: Administrator access is also extremely limited:

- Admin Center: In general, the deleted subscription will no longer appear in the Admin Center for that tenant. If the entire tenant (Azure AD) is deleted, the global admin account used for that tenant is also gone, so even the admin cannot sign in to that tenant’s portal anymore[1].

- If the Azure AD is not deleted (for example, if the organization had other separate subscriptions like an Azure subscription or a different Microsoft 365 subscription still using that same directory), then the admin can still log in to the Azure AD and see that the Business Premium subscription object is in a deleted state. But none of the data from the subscription is accessible – the Exchange, SharePoint, etc. data has been wiped.

- Essentially, admins can only use the admin center to manage other active subscriptions or to purchase a new subscription if they want to start over[1]. They cannot recover anything related to the deleted subscription. Microsoft’s documentation states that once deleted, the subscription cannot be reactivated or restored[1].

Data Status: All customer data is permanently deleted at this stage:

- Microsoft purge operations will have been executed to remove Exchange mailboxes, SharePoint site collections, OneDrive content, Teams chat data, and any other stored information for the tenant[2]. The data is no longer available on Microsoft’s servers. It is irrecoverable by any means.

- Additionally, the Microsoft Entra ID (Azure Active Directory) for the tenant is removed (if that directory isn’t being used by another subscription)[1]. This means the actual tenant identification is gone – all user objects, groups, and any Azure AD-integrated applications in that directory are deleted.

- Note: If the Azure AD was shared with another service (like if you had an Azure subscription without M365, or if you activated some separate service on the same tenant), Microsoft might not delete the directory itself. Instead, they would just remove all Microsoft 365 service data and leave the bare directory. In that scenario, the global admin account might still exist as a user in Azure AD, but with no licenses. However, all data (mail, files) is still wiped.

- Backups: Microsoft generally does not retain backups once a tenant is deleted beyond what might exist for disaster recovery on their side (and those are not accessible to customers). So effectively, anything not already saved by the admin before deletion is lost. Even support cannot bring back a tenant that has passed this point.

- Domain Names: If the organization was using a custom domain with Microsoft 365 (e.g., companyname.com for email addresses), after deletion, that domain will eventually be released from the old tenant. Typically, within a few days of tenant deletion, the domain becomes free to use on another tenant. This could be relevant if you plan to set up a new M365 tenant and reuse the same email domain.

Administrator Actions at Deleted stage: Ideally, you do not want to reach this stage without preparation. Once in Deleted status, options are extremely limited:

- New Subscription: The only path forward, if you want to use Microsoft 365 again, is to start a new subscription/tenant. This would be essentially starting from scratch – you’d get a new tenant ID (or possibly register the old domain if it’s freed up) and manually import any data you saved. Microsoft explicitly notes

ntally allowed a lapse has no recourse beyond this point.

Additional Considerations

Notifications and Pre-Expiration Warnings (Admin Perspective)

Administrators will receive several notifications as the renewal date approaches. In the Microsoft 365 admin center, warnings typically start appearing as the subscription nears its end. According to Microsoft, admins receive a series of email and in-portal notifications prior to expiration[1]. These might include messages like “Your subscription will expire on \. Please renew to avoid interruption.” While the exact cadence isn’t specified publicly, many admins report getting notices roughly 30 days out, 7 days out, and at expiration, among others. It’s crucial for admins to ensure their contact info is up to date in the tenant, so these notices are received.

End users, on the other hand, do not typically get an “expiration” notification from Microsoft (unless an admin communicates it or if their Office apps show a small warning). Microsoft’s notifications about subscription status are directed to admins, not end-users. The first time an end-user might see an automated notice is if their Office apps go unlicensed in the Disabled stage, which results in a banner prompting for login/renewal. Therefore, it is the admin’s responsibility to communicate with users if a lapse is expected.

Impact on Different Services and Data Types

As outlined earlier, all major services are affected, but here’s a quick recap of how various data types/services behave through the stages:

- Exchange Email: During Expired (grace), email is fully functional[2]. During Disabled, mailboxes are inaccessible to users and email flow is halted (messages to/from users will not be delivered)[2]. The data in the mailbox remains stored though, until deletion. At Deleted stage, mailbox data is gone permanently. If there were any special mail archiving or journaling in place, those too are gone unless handled externally.

- OneDrive and SharePoint files: During Expired, all files and SharePoint content can be accessed and edited normally by users. During Disabled, the content is read-only and only accessible to admins (users can’t access their OneDrives or SharePoint sites at all)[2]. No data deletion happens until the final stage; then at Deleted, all files and site content are purged from SharePoint/OneDrive storage.

- Microsoft Teams: Teams relies on other services (Exchange for chat storage, SharePoint for files). In Expired, Teams chats, calls, and filesharing work normally. In Disabled, Teams is non-functional for users – they cannot login to the Teams app or attend meetings via their account. Messages sent to them will fail. The data (chat history, Team sites) is retained in the backend but nobody can use Teams in the organization. By Deleted, all Teams data is removed (any Team sites are SharePoint sites, which are deleted; chat data in mailboxes is deleted).

- Other Office apps (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, etc.): In Expired, the desktop apps continue to work normally (since the user’s license is technically still considered valid during grace). In Disabled, if a user tries to use an Office desktop app, it will detect an inactive license and switch to read-only mode[1] (documents can be opened or printed, but not edited or saved). Web versions of Office apps won’t be usable at all because login is blocked. At Deleted, of course, the apps can’t be used through that account (the user would have to sign in with a different active license or use another means).

- SharePoint Online site functionality: If your Business Premium tenant had any SharePoint Online intranet or site pages, those follow the same rule: accessible in Expired, no access in Disabled (effectively offline, though admins could pull data out via SharePoint admin), and deleted at the end. If external users had access to any content (via sharing links), those links would stop working once Disabled hits because the content is locked down, and obviously cease completely after deletion.

- Azure AD data: While not “user content”, it’s worth noting the status of your Azure AD. In Expired and Disabled, the Azure AD (user accounts, groups) still exists. You could even perform some Azure AD tasks (like resetting passwords or adding guest users) in Disabled, but they won’t have effect on usage until a renewal. At deletion, if your Azure AD is not used by any other subscription, it gets deleted along with all the user accounts[1]. If your Azure AD was linked to other active services (like an Azure subscription, or if you had multiple Microsoft 365 subscriptions and only one expired), then the Azure AD itself may remain, but the accounts’ ties to the expired subscription are removed. In a pure single-subscription scenario, Azure AD goes away with the tenant deletion.

- Licenses and add-ons: Any additional licenses (like add-on licenses or other service subscriptions attached to users) will also expire or become non-functional in line with the main subscription. For example, if you had a premium third-party app in Teams or an Azure Marketplace app that relies on the tenant, those would also cease when the main tenant is disabled/deleted.

There are generally no differences in the process for different data types – all customer data is treated the same in the retention and deletion timeline[5]. The key difference is just in how the user experiences the loss of access for each service. But ultimately, whether it’s an email or a file or a chat message, it will be preserved through the Disabled stage and wiped at the Deleted stage.

Best Practices for Administrators at Each Stage

Managing a subscription that’s expiring requires planning. Here are best practices and action items for admins:

- Before Expiration (Active stage):

- Keep an eye on renewal dates. Mark your calendar well in advance of your renewal deadline, especially if you have recurring billing off.

- Enable auto-renewal if appropriate, to avoid accidental lapses[2]. If you intentionally don’t want to renew, plan for that decision rather than letting it catch you off guard.

- Notify finance or decision-makers in your organization as the date approaches so that the renewal can be approved or alternative plans made.

- If you know you will not renew, formulate a data migration plan ahead of time (e.g., moving to another platform or archiving data).

- Expired Stage (0–30 days after end):

- Renew promptly if you intend to continue. There’s no benefit to waiting, and renewing will remove the “expired” status and keep users from ever seeing any disruption[1].

- If not renewing, begin data backup tasks immediately (don’t wait until day 29). Copy critical files, export mailboxes, etc., while everything is easily accessible. This 30-day window is the most convenient time to get data out.

- Monitor the grace period timeline. Know when that 30 days is up. Microsoft may show a countdown in the admin center. You don’t want to accidentally slip into Disabled if you didn’t mean to.

- Inform key staff: if not renewing, leadership and IT staff should know the exact date when users will lose access (day 30). You might hold off telling all end-users until closer to the Disabled date to avoid confusion, but your IT helpdesk should be prepared.

- Disabled Stage (30–120 days after):

- If you haven’t yet renewed but still want to, this is the last chance – reactivate the subscription as soon as possible to restore service[1].

- If you’re in this stage intentionally (to finish migration or because of finances), accelerate your backup/export efforts. You have up to 90 days, but it’s wise to complete backups well before the final deadline in case of any issues or large data volumes to export.

- Manage communications: At the start of the Disabled stage, you should communicate with end-users that the service is now suspended. Likely they will already be alerting you since they can’t access email or Teams. Provide them guidance if they need any data (though they themselves can’t access it now, you might fulfill requests by retrieving data for them).

- Security consideration: Even though users can’t access, their accounts still exist in Azure AD. It might be prudent to ensure MFA is enabled or accounts are protected in case someone tries to misuse the situation. Generally, though, since login won’t grant access to data, this is a minor concern.

- Consider alternate solutions: If your organization only needs some parts of M365, consider whether you can purchase a smaller plan to maintain minimal access. For example, if email data retention is legally required, buying a few Exchange Online Plan 1 licenses for key mailboxes and reactivating the tenant under that could be a strategy. This must be done before deletion.

- Approaching Deletion (~120 days):

- Double-check that all required data is backed up. Ensure you have downloaded everything vital – you won’t get another chance.

- If you are on the fence about needing something, it’s better to back it up now. Even if it’s large (like a SharePoint document library), export it.

- Verify backups: Open some PST files, try restoring a document from backup to make sure your backups are not corrupted.

- Remind decision-makers that the drop-dead date is coming. Sometimes seeing “your data will be unrecoverable after X date” motivates a final decision to either renew or accept the loss.

- Post-Deletion:

- If you’ve moved away from Microsoft 365, ensure you have a secure storage for the data you exported (since it may contain sensitive emails, etc., outside of Microsoft’s protected cloud).

- If you are starting a new platform, begin importing that data as needed.

- Clean up any decommissioning tasks (like uninstalling Office software from devices if you’re no longer licensed, etc.)

- Reflect on the process and ensure any future critical cloud subscriptions are tracked so that expirations are handled more smoothly.

In general, the best practice is to avoid reaching the Disabled/Deleted stages unintentionally. If you plan to keep using Microsoft 365, renewing before day 30 is ideal to prevent any user impact. If you plan to leave, use the provided time to cleanly extract your data. Communication and planning are key to avoid panic when users lose access.

Compliance and Legal Hold Considerations