Executive Summary

The contemporary cybersecurity landscape necessitates robust application control mechanisms to safeguard organizational assets. While foundational methods, such as basic AppLocker configurations, offer some degree of application restriction, they often fall short against sophisticated modern threats. This report details a more comprehensive approach for preventing unauthorized applications from executing on Windows devices, leveraging the advanced capabilities of Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC) in conjunction with Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) rules. This strategy is particularly pertinent for Small and Medium Businesses (SMBs) utilizing Microsoft 365 Business Premium.

The core recommendation involves implementing WDAC through a stringent whitelisting methodology, meticulously refined via an audit-first deployment strategy, and fortified by complementary ASR rules. This layered defence provides superior protection against emerging threats, including zero-day exploits and ransomware, by significantly reducing the attack surface. Although the initial configuration may require a dedicated investment of time and resources, this proactive posture ultimately minimizes long-term operational overhead and enhances the overall security posture for SMBs, which often operate with limited dedicated IT security personnel.

Understanding Application Control: Beyond Basic Intune AppLocker

Effective application control is a cornerstone of modern cybersecurity. The method described in some basic guides, often relying on AppLocker, represents an initial step but is increasingly insufficient for the complexities of today’s threat landscape. A more advanced and resilient approach is imperative.

Limitations of Traditional AppLocker

The referenced blog post likely outlines a basic AppLocker configuration managed through Microsoft Intune. While AppLocker facilitates the blocking of applications based on attributes such as publisher, file path, or cryptographic hash, it possesses inherent limitations that diminish its efficacy against contemporary threats.[1, 2] AppLocker, introduced with Windows 8, is an older technology primarily designed for management via Group Policy.[3, 4] Microsoft’s strategic direction indicates a cessation of new feature development for AppLocker, with only security fixes being provided. This signals its eventual obsolescence as a primary application control solution.

A critical deficiency of AppLocker is its primary operation in user mode, rendering it incapable of blocking kernel-mode drivers. This limitation creates a significant security vulnerability, as many advanced threats operate at the kernel level to evade detection and maintain persistence. Furthermore, while AppLocker policies can be granularly targeted to specific users or groups—a feature useful for shared device scenarios—WDAC policies are fundamentally device-centric, offering a more consistent and robust security posture across the entire endpoint.[2, 5]

Introduction to Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC)

Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC), formerly known as Device Guard, represents Microsoft’s modern and significantly more robust application control solution, introduced with Windows 10.[3, 6] WDAC is engineered as a core security feature under the rigorous servicing criteria defined by the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC), underscoring its critical role in endpoint protection.

Fundamentally, WDAC operates on the principle of application whitelisting. This means that, by default, only applications explicitly authorized by the organization are permitted to execute, thereby drastically reducing the attack surface available to malicious actors.[6] This contrasts sharply with blacklisting, which attempts to identify and block known malicious applications, a reactive approach that is inherently vulnerable to unknown or zero-day threats.[7, 8] WDAC’s proactive stance provides a robust defense against malware propagation and unauthorized code execution.

Beyond the fundamental shift to whitelisting, WDAC offers advanced capabilities absent in AppLocker. These include the ability to enforce policies at the kernel level, integrate with reputation-based intelligence via the Intelligent Security Graph (ISG), provide COM object whitelisting, and support application ID tagging.[4, 9] WDAC is also fully compatible with Microsoft Intune, which streamlines the deployment and enforcement of these sophisticated application control policies across managed devices, making it an ideal solution for organizations leveraging Microsoft 365 Business Premium.[6, 10]

The transition from AppLocker’s implicit blacklisting to WDAC’s explicit whitelisting signifies a fundamental shift in Microsoft’s security philosophy towards a Zero Trust model.[6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13] This is not merely a feature upgrade; it represents a paradigm shift from a reactive “clean up after an attack” mindset to a proactive “prevent attacks from executing” posture. For SMBs, this is particularly advantageous, as prevention is considerably less resource-intensive than remediation, which is crucial for environments with limited dedicated security staff. WDAC’s default-deny stance inherently protects against unknown (zero-day) threats, a major advantage over traditional antivirus or blacklisting approaches.[6, 8]

Microsoft’s clear endorsement of WDAC as the future of application control is evident in its continuous improvements and planned support from Microsoft management platforms, while AppLocker will only receive security fixes and no new features. This strategic direction means that investing time and effort into WDAC now aligns SMBs with Microsoft’s long-term security roadmap, ensuring their application control strategy remains effective and supported. This proactive adoption helps avoid the technical debt associated with implementing a solution that will not evolve to counter new threats.

Table 1: AppLocker vs. WDAC Comparison

| Feature/Aspect |

AppLocker |

WDAC |

| OS Support |

Windows 8 and later |

Windows 10, Windows 11, Windows Server 2016+ |

| Core Principle |

Blacklisting (Default Allow, Block Known Bad) |

Whitelisting (Default Deny, Allow Only Known Good) |

| Kernel Mode Control |

No |

Yes (Blocks kernel-mode drivers) |

| New Feature Development |

Security Fixes Only |

Active Development & Continual Improvements |

| Management Integration |

Group Policy (Primary), Limited Intune |

Microsoft Intune (Preferred), Configuration Manager, Group Policy |

| Reputation-Based Trust |

No |

Yes (Intelligent Security Graph – ISG) |

| Managed Installer Support |

No |

Yes (Automates trust for Intune-deployed apps) |

| Policy Scope |

User/Group |

Device |

| Attack Surface Reduction |

Less Comprehensive |

More Comprehensive (Blocks unauthorized code execution, including zero-day exploits) |

| Zero-Day Protection |

Limited |

Strong (Default-deny approach prevents unknown threats) |

Core Concepts of WDAC for SMBs

Implementing WDAC effectively requires a foundational understanding of its operational principles and the various rule types that govern application execution. These concepts are crucial for SMBs to design and deploy a robust application control strategy.

The Principle of Application Whitelisting

WDAC fundamentally operates on an “allow-by-default” principle for explicitly trusted applications, and a “deny-by-default” for all other executables.[6] This approach is the inverse of blacklisting, which attempts to block known malicious items.[7] By adopting a whitelisting model, WDAC significantly reduces the attack surface, ensuring that only authorized software can execute. This minimizes the risk of malware propagation and unauthorized code execution, including protection against zero-day exploits, which are unknown to traditional signature-based defenses.[6] For SMBs, this proactive defense is invaluable, as it prevents threats from gaining a foothold, thereby reducing the burden on limited IT resources for incident response and remediation.

Detailed Explanation of WDAC Rule Types

WDAC policies define the criteria for applications deemed safe and permitted to run, establishing a clear boundary between trusted and untrusted software.[6] WDAC provides administrators with the flexibility to specify a “level of trust” for applications, ranging from highly granular (e.g., a specific file hash) to more general (e.g., a certificate authority).[14]

-

- Publisher Rules (Certificate-based policies): These rules allow applications signed with trusted digital certificates from specific publishers.[6, 9, 14] This rule type combines the PcaCertificate level (typically one certificate below the root) and the common name (CN) of the leaf certificate.[14] Publisher rules are ideal for trusting software from well-known, reputable vendors such as Microsoft or Adobe, or for device drivers from Intel.[14] A significant benefit is reduced management overhead; when software updates are released by the same publisher, the policy generally does not require modification.[14] However, this level of trust is broader than a hash rule, meaning it trusts all software from a given publisher, which might be a wider scope than desired in highly sensitive environments.

-

- Path Rules: Path rules permit binaries to execute from specified file path locations.[6, 9, 14] These rules are applicable only to user-mode binaries and cannot be used to allow kernel-mode drivers.[14] They are particularly useful for applications installed in directories typically restricted to administrators, such as

Program Files or Windows directories.[5, 14] WDAC incorporates a runtime user-writeability check to ensure that permissions on the specified file path are secure, only allowing write access for administrative users.[14] It is crucial to note that path rules offer weaker security guarantees compared to explicit signer rules because they depend on mutable file system permissions. Therefore, their use should be avoided for directories where standard users possess the ability to modify Access Control Lists (ACLs).[9, 14]

-

- Hash Rules: Hash rules specify individual cryptographic hash values for each binary.[6, 9, 14] This constitutes the most specific rule level available in WDAC.[14] While providing the highest level of control and security, hash rules demand considerable effort for maintenance.[14] Each time a binary is updated, its hash value changes, necessitating a corresponding update to the policy.[14] WDAC utilizes the Authenticode/PE image hash algorithm, which is designed to omit the file’s checksum, Certificate Table, and Attribute Certificate Table. This ensures the hash remains consistent even if signatures or timestamps are altered or a digital signature is removed, thereby offering enhanced security and reducing the need to revise policy hash rules when digital signatures are updated.[14] Hash rules are essential for unsigned applications or when a specific version of an application must be allowed irrespective of its publisher.

-

- Managed Installer: This policy rule option automatically allows applications installed by a designated “managed installer”.[9, 14, 15, 16, 17] The Intune Management Extension (IME) can be configured as a managed installer.[15, 16] When IME deploys an application, Windows actively observes the installation process and tags any spawned processes as trusted.[15] This feature significantly simplifies the whitelisting process for applications deployed via Intune, as these applications are automatically trusted without requiring explicit, manual rule creation.[15, 16] A key limitation is that this setting does not retroactively tag applications; only applications installed after enabling the managed installer will benefit from this mechanism.[16] Existing applications will still require explicit rules within the WDAC policy.

-

- Intelligent Security Graph (ISG) Authorization: The ISG authorization policy rule option automatically allows applications with a “known good” reputation, as determined by Microsoft’s Intelligent Security Graph.[9, 14, 17] The ISG leverages real-time data, shared threat indicators, and broader cloud intelligence to continuously assess application reputation.[12] This capability reduces the need for manual rule creation for widely used, reputable software [5, 14] and helps minimize false positives by trusting applications broadly recognized as safe.[12] However, organizations requiring the use of applications that might be blocked by the ISG’s assessment should utilize the WDAC Wizard to explicitly allow them or consider third-party application control solutions.[18] The “Enabled:Invalidate EAs on Reboot” option can be configured to periodically revalidate the reputation for applications previously authorized by the ISG.[14, 17]

Table 2: WDAC Rule Types and Their Application (Pros & Cons)

| Rule Type |

Description |

Pros for SMBs |

Cons for SMBs |

Best Use Case for SMBs |

| Publisher |

Allows apps signed by trusted digital certificates from specific publishers. |

Low maintenance for updates from same vendor; broad trust for reputable software. |

Less granular; trusts all software from a given publisher. |

Core business applications from major, trusted software vendors (e.g., Microsoft Office, Adobe). |

| Path |

Allows binaries to run from specific file path locations. |

Simple to configure for applications in secure, admin-writeable directories. |

Less secure than signer rules; relies on file system permissions; only for user-mode. |

Applications installed in Program Files, Windows directories, or other paths where standard users cannot modify ACLs. |

| Hash |

Specifies individual cryptographic hash values for each binary. |

Highest level of control and security; essential for unsigned or specific versions. |

High maintenance; requires policy updates for every binary change. |

Highly sensitive custom line-of-business applications; specific versions of software; unsigned utilities. |

| Managed Installer |

Automatically allows apps installed by a designated managed installer (e.g., Intune Management Extension). |

Greatly simplifies whitelisting for Intune-deployed applications; reduces manual effort. |

No retroactive tagging for pre-existing apps; reliance on installer integrity. |

All software deployed and managed through Microsoft Intune. |

| Intelligent Security Graph (ISG) |

Automatically allows apps with a “known good” reputation as defined by Microsoft’s ISG. |

Reduces manual rule creation for widely used, reputable software; minimizes false positives. |

Relies on Microsoft’s reputation service; may block niche or internal apps; periodic revalidation needed. |

Widely used commercial software with established reputations; general productivity tools. |

Understanding Base and Supplemental WDAC Policies

WDAC supports two policy formats: the older Single Policy format, which permits only one active policy on a system, and the recommended Multiple Policy format, supported on Windows 10 (version 1903 and later), Windows 11, and Windows Server 2022.[9] The multiple policy format offers enhanced flexibility for deploying Windows Defender Application Control.

This flexibility is manifest in two key policy types:

-

- Base Policies: These policies define the fundamental set of trusted applications that are permitted to run across devices.[9, 16] They establish the core security baseline.

-

- Supplemental Policies: These policies are designed to expand the scope of trust defined by a base policy without altering the base policy itself.[9, 16] Supplemental policies are particularly useful for accommodating specific departmental software, unique line-of-business applications, or different user personas (e.g., HR, IT departments) within an organization.[9, 17]

The multiple policy format also enables “enforce and audit side-by-side” scenarios, where an audit-mode base policy can be deployed concurrently with an existing enforcement-mode base policy. This capability is invaluable for validating policy changes before full enforcement, minimizing the risk of operational disruption.[9] For growing SMBs, this modular approach provides significant flexibility, allowing them to establish a broad, stable base policy and then add specific allowances as needed without compromising the core security posture or requiring extensive reconfigurations.

While hash rules offer the highest security granularity, they demand constant updates, creating a considerable maintenance burden.[14] In contrast, publisher rules, though less granular, significantly reduce maintenance efforts.[14] The Managed Installer and ISG features further automate the trust process, reducing manual intervention.[14] This illustrates a clear trade-off between the level of security granularity and the associated management overhead. For SMBs, a pragmatic approach involves prioritizing Publisher rules for major software vendors and extensively leveraging the Managed Installer for applications deployed via Intune, along with ISG for common, reputable software, to minimize manual effort. Hash rules should be reserved judiciously for critical, static, or unsigned line-of-business applications where the highest assurance is indispensable, acknowledging the increased maintenance requirement. This pragmatic strategy balances robust security with the practical constraints of limited IT resources.

WDAC’s default-deny nature means that any application not explicitly allowed will be blocked.[6] This characteristic can be highly disruptive if not meticulously planned and tested.[7, 8] The concepts of “audit mode” and “iterative refinement” directly address this challenge.[9, 17, 19, 20] The initial setup of a comprehensive whitelist can be time-consuming and may encounter user resistance.[7] Therefore, a phased approach, commencing with audit mode, is not merely a best practice but a fundamental necessity for SMBs. This approach prevents legitimate business operations from being crippled and facilitates user acceptance. The iterative process allows for gradual policy hardening, reducing the risk of unexpected disruptions and fostering a smoother transition to a more secure environment.

Step-by-Step Implementation of WDAC with Microsoft Intune

Implementing WDAC policies requires careful planning and execution within the Microsoft Intune environment. The following steps provide a practical guide for SMBs to configure and deploy WDAC.

Prerequisites and Licensing for WDAC

Before initiating WDAC deployment, several prerequisites must be met:

-

- Microsoft 365 Business Premium: This subscription is essential as it includes Microsoft Intune Plan 1 and Microsoft Defender for Business, which are foundational for managing WDAC policies.[21, 22]

-

- Windows Versions: WDAC policies are supported on modern Windows operating systems. Specifically, Windows 10 (version 1903 or later with KB5019959) and Windows 11 (version 21H2 with KB5019961, or version 22H2 with KB5019980) are compatible.[16]

-

- Windows Professional Support: A significant development for SMBs is that WDAC policy creation and deployment are now fully supported on Windows 10/11 Professional editions, eliminating previous Enterprise/Education SKU licensing restrictions.[23] This makes WDAC highly accessible for SMBs operating with Business Premium licenses.

-

- Intune Enrollment: All target devices must be enrolled in Microsoft Intune to receive and enforce WDAC policies.[16, 18]

-

- Permissions: Accounts performing these configurations must possess the “App Control for Business” permission within Intune, which includes rights for creating, updating, and assigning policies. Additionally, “Intune Administrator” privileges may be required for enabling the managed installer feature.[16] Microsoft advises adhering to the principle of least privilege by assigning roles with the fewest necessary permissions to enhance organizational security.[16]

Enabling the Managed Installer in Intune

The Managed Installer feature is crucial for streamlining WDAC policy management by automatically trusting applications deployed via the Intune Management Extension (IME), thereby reducing the need for manual whitelisting efforts.[15, 16]

Step-by-Step Instructions:

-

- Sign in to the Microsoft Intune admin center at https://intune.microsoft.com.

- Navigate to Endpoint security > App control for Business (Preview).

- Select the Managed Installer tab.

- Click Add, then click Add again after reviewing the instructions.[10]

- This action is a one-time event for the tenant.[16]

It is important to understand that this setting does not retroactively tag applications. Only applications installed after the managed installer feature is enabled will be automatically trusted by this mechanism.[16] Existing applications on devices will require explicit rules within the WDAC policy to be permitted.

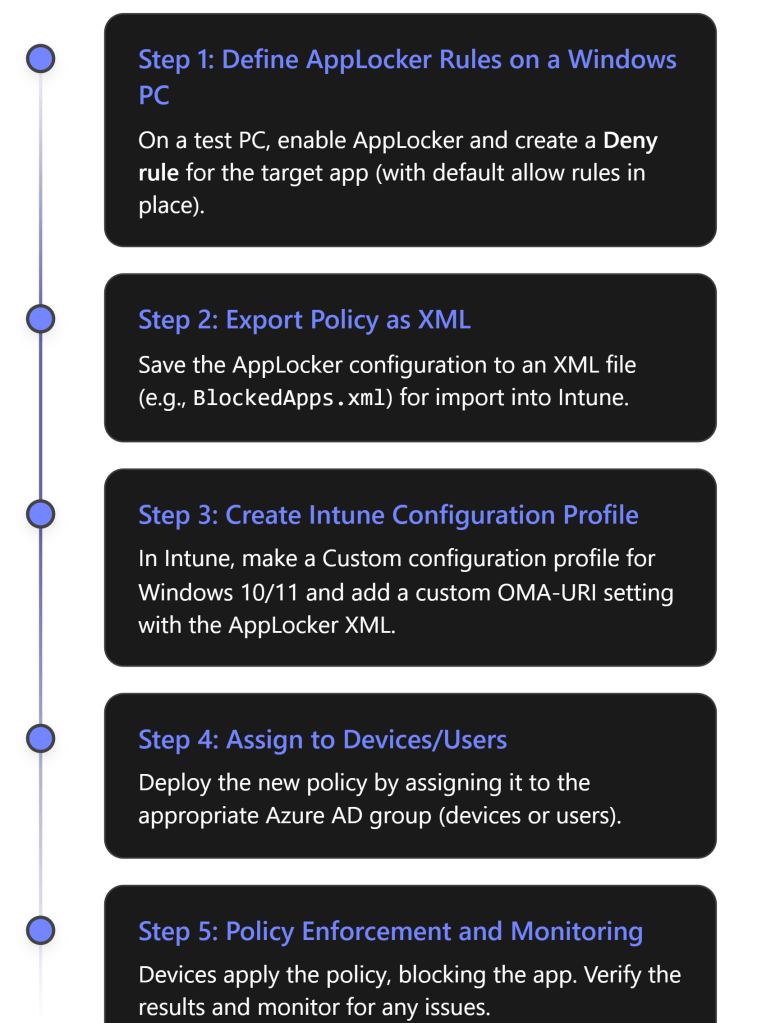

Creating a WDAC Base Policy using the WDAC Wizard

The WDAC Wizard is the recommended and most user-friendly tool for creating WDAC policies, particularly for SMBs that may not possess extensive PowerShell expertise.[9, 10, 15, 24, 25] The wizard simplifies the process by generating the necessary XML data for the policy.[10]

Step-by-Step Instructions:

-

- Download the WDAC Wizard from https://webapp-wdac-wizard.azurewebsites.net/.[10, 15, 25]

- Open the wizard and click Policy Creator, then Next.

- Ensure that Multiple Policy Format and Base Policy are selected (these are typically the default options), then click Next.[10]

- Select a base template. For SMBs, “Signed and Reputable Mode” is an excellent starting point, as it inherently trusts Microsoft-signed applications, Windows components, Store applications, and applications with a good reputation as determined by the Intelligent Security Graph (ISG).[5, 10] Alternatively, “Default Windows Mode” allows Windows in-box kernel and user-mode code to execute.[17, 23]

- On the subsequent page, review and enable desired options. For SMBs, ensuring “Managed Installer” and “Intelligent Security Graph Authorization” are turned on is highly beneficial. Crucially, select Audit Mode for the initial deployment; this is strongly recommended for testing purposes.[9, 10, 16, 17, 19, 26, 27]

- Click Next to initiate the policy build. The wizard will propose Microsoft trusted publisher rules.[15]

- Upon completion, the wizard will provide the file path to download both the

.cip (binary) and .xml files, typically located in C:\Users\\Documents.[10]

Deploying the WDAC Policy via Intune

Once the WDAC policy XML file is generated, it can be deployed to managed devices through Microsoft Intune.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

-

- Return to the Microsoft Intune admin center.

- Navigate to Endpoint security > App Control for Business (Preview).

- Select the App Control for Business tab, then click Create Policy.

- On the Basics tab, enter a descriptive Name for the policy (e.g., “SMB Base WDAC Policy – Audit Mode”) and an optional Description.[10, 16]

- On the Configuration settings tab, select the Enter xml data option.

- Browse to the

.xml file generated by the WDAC Wizard and upload it.[10]

- (Optional) If applicable, use Scope tags for managing policies in distributed IT environments.[10]

- On the Assignments tab, assign the profile to a security group containing the Windows devices targeted for WDAC implementation.[10] For initial deployment, it is critical to assign the policy to a small pilot group while still in audit mode.[17, 19]

- Review the settings on the Review + create tab, then click Create to deploy the policy.

It is important to note that while the WDAC Wizard provides both XML and binary (.cip) policy files, Intune handles the deployment of the binary policy automatically once the XML is uploaded.[19]

Strategies for Creating and Deploying Supplemental Policies

Supplemental policies are designed to extend the trust defined by a base WDAC policy for specific applications or user groups without modifying the core base policy.[9, 16] This modularity is particularly beneficial for SMBs managing line-of-business (LOB) applications or unique software requirements.

Method for creating and deploying supplemental policies:

-

- Creation with WDAC Wizard: Supplemental policies are also created using the WDAC Wizard.[9, 15] When creating a new policy in the wizard, select “Supplemental Policy” and specify the base policy it will augment.

- Rule Generation: Scan specific application installers or folders (e.g.,

D:\GetCiPolicy\testpackage) to generate rules tailored for those applications.[15] For signed applications, the “Publisher” rule level is preferred; for unsigned applications or to allow a highly specific version, the “Hash” rule level is appropriate.[24]

- Export and Deployment: Export the supplemental policy XML file. Deploy this supplemental policy via Intune following the same procedure as a base policy, assigning it to the relevant device groups.

This modular approach simplifies management for SMBs. Instead of maintaining a single, complex policy, organizations can leverage a stable base policy and introduce smaller, targeted supplemental policies for unique application requirements. This design makes policy updates and troubleshooting more manageable and less prone to unintended disruptions.

Whitelisting inherently requires that every allowed application has a defined rule, which can be a high-maintenance task.[7, 8] The Managed Installer feature directly addresses this challenge by automatically trusting applications deployed through the Intune Management Extension.[15, 16] This establishes a trusted “pipeline” for software distribution, significantly reducing the manual effort involved in maintaining WDAC policies. For SMBs with limited IT staff, manually creating and updating rules for every application is often impractical. By leveraging the Managed Installer, a substantial portion of application deployments can be automatically trusted, drastically lowering the ongoing management burden of WDAC and making a comprehensive whitelisting strategy feasible for smaller organizations.

The default-deny nature of WDAC means that misconfiguration can inadvertently block essential business applications.[7] Microsoft consistently recommends deploying WDAC policies in “audit mode” first.[9, 10, 16, 17, 19, 20, 26, 27] This mode logs potential blocks without enforcing them, allowing for meticulous policy refinement.[20, 26] For SMBs, where business continuity is paramount, a sudden, full enforcement of WDAC without prior auditing could cripple operations, leading to significant downtime and user frustration. The “audit first” approach is a critical risk mitigation strategy, enabling IT administrators to identify and address false positives before they impact productivity. This cautious progression also improves user acceptance and buy-in by minimizing unexpected disruptions to their workflows.[12]

Best Practices for WDAC Policy Refinement (Audit Mode & Monitoring)

The successful implementation of WDAC policies hinges on a meticulous refinement process, primarily conducted through audit mode, and supported by robust monitoring capabilities. This iterative approach is crucial for minimizing operational impact and ensuring policy effectiveness.

The Critical Role of Audit Mode in Policy Development

Audit mode serves as a vital phase in WDAC policy development, allowing IT administrators to assess the potential impact of a policy on their environment without actively blocking applications.[16, 17, 19, 26, 27, 28] In this mode, WDAC generates logs for any application, file, or script that would have been blocked if the policy were in enforced mode.[20, 26]

For SMBs, this “test before block” methodology is indispensable. It enables the discovery of legitimate applications, binaries, and scripts that might have been inadvertently omitted from the policy and thus should be included.[20] This proactive identification of potential conflicts helps prevent unexpected disruptions to business operations and significantly reduces user complaints and help desk tickets.[12] The policy refinement process is inherently iterative: deploy in audit mode, meticulously monitor events, refine the policy based on observations, and repeat this cycle until the desired outcome is achieved, characterized by minimal unexpected audit events.[9, 17, 20]

Collecting and Analyzing WDAC Audit Events

Effective policy refinement relies on comprehensive collection and analysis of WDAC audit events.

Local Event Viewer

All WDAC events are logged locally within the Windows Event Log. The primary logs to monitor are:

-

Microsoft-Windows-CodeIntegrity/Operational: This log captures events related to binaries.[9, 20]

-

Microsoft-Windows-AppLocker/MSI and Script: This log records events pertaining to scripts and MSI installers.[9, 20]

Key Event IDs to focus on in Audit Mode:

-

- Event ID 3076: This event indicates an action that would have been blocked by a WDAC policy if it were enforced.[20]

-

- Event ID 8028: This event signifies an action that would have been blocked by an AppLocker (MSI and Script) policy if it were enforced.[20]

To access these logs, administrators can open the Windows Event Viewer and navigate to Applications and Services Logs > Microsoft > Windows, then locate the CodeIntegrity and AppLocker logs.[29]

Centralized Monitoring with Azure Monitor / Log Analytics

For enhanced scalability and centralized management, particularly as an SMB expands, collecting these events in an Azure Monitor Log Analytics Workspace is highly recommended.[9, 20, 26, 30]

Prerequisites for centralized monitoring:

-

- Azure Monitor Agent (AMA): The AMA must be deployed to the Windows devices from which events are to be collected.[20] The AMA installer can be packaged as a Win32 application and deployed efficiently via Intune.[20]

-

- Visual C++ Redistributable 2015 or higher: This is a prerequisite for the AMA and should be deployed as a dependency.[20]

-

- Azure Log Analytics Workspace: An active Log Analytics Workspace is required as the destination for collected events.

Creating a Data Collection Rule (DCR) in Azure:

-

- Open the Azure portal and navigate to Monitor > Data Collection Rules, then click Create.[20]

- On the Basics page, provide a descriptive Rule Name, select the appropriate Subscription, Resource Group, and Region, and choose Windows as the Platform Type. Click Next: Resources.[20]

- On the Resources page, add the specific devices or resource groups where AMA is deployed. Click Next: Collect and deliver.[20]

-

- On the Collect and deliver page, click Add data source.[20]

-

- For Data source type, select Windows event logs.

-

- Select Custom and provide the XPath queries:

Microsoft-Windows-CodeIntegrity/Operational!* and Microsoft-Windows-AppLocker/MSI and Script!* to filter and limit data collection to relevant events.

-

- On the Destination tab, select the Destination type, Subscription, and Account or namespace for your Log Analytics Workspace.[20]

-

- Review the configuration on the Review + create page, then click Create.[20]

Kusto Query Language (KQL) for Analysis:

Once event logs are ingested into Log Analytics, KQL queries can be used to filter and analyze the data effectively.[20, 26]

Example KQL for Event ID 3076 (Code Integrity Audit Events):

Event

| where EventLog == 'Microsoft-Windows-CodeIntegrity/Operational' and EventID == 3076

| extend eventData = parse_xml(EventData).DataItem.EventData.Data

| extend fileName = tostring(eventData.['#text']) // File name of the blocked executable

| extend filePath = tostring(eventData.['#text']) // File path of the blocked executable

| extend fileHash = tostring(eventData.['#text']) // Hash of the blocked executable

| extend policyName = tostring(eventData.['#text']) // Name of the WDAC policy that would have blocked it

| project TimeGenerated, Computer, UserName, fileName, filePath, fileHash, policyName

Note: The exact indices for eventData elements (e.g., eventData, eventData) may vary based on the specific XML structure within the EventData column in your environment. Administrators should verify the correct indices by inspecting raw event data in Log Analytics.

Similar queries can be constructed for Event ID 8028 from the AppLocker log. The power of KQL lies in its ability to perform powerful filtering, aggregation, and visualization of audit data, making it easier to identify patterns of blocked applications and prioritize policy adjustments.[26]

Table 3: Key Event IDs for WDAC Audit Log Analysis

| Event Log Name |

Event ID |

Description |

Significance in Audit Mode |

Actionable Insight |

Microsoft-Windows-CodeIntegrity/Operational |

3076 |

An application or driver would have been blocked by a WDAC policy. |

Identifies legitimate executables or drivers that are not yet allowed by the policy. |

Add Publisher, Path, or Hash rules to the WDAC policy for this application/driver. |

Microsoft-Windows-AppLocker/MSI and Script |

8028 |

An MSI or script would have been blocked by an AppLocker policy. |

Identifies legitimate scripts or installers that are not yet allowed by the policy. |

Add corresponding rules (e.g., Publisher, Path, Hash) to the WDAC or AppLocker policy. |

Iterative Process for Policy Refinement and Testing

The refinement of WDAC policies is an ongoing, iterative cycle:

-

- Analyze Audit Logs: Regularly review the collected audit events (from Event Viewer or Log Analytics) to identify legitimate applications or processes that are being flagged for blocking.[9, 20]

- Create Exceptions: Based on the audit log analysis, use the WDAC Wizard to generate new rules (Publisher, Path, or Hash) or create supplemental policies to explicitly allow these legitimate applications.[9, 15]

- Redeploy in Audit Mode: Deploy the updated policy (or supplemental policy) back to the pilot group in audit mode. This step is crucial to ensure that the newly added rules are effective and that no new, unexpected blocks occur.[9, 17, 19]

- Monitor and Repeat: Continue this cycle of monitoring, refining, and redeploying in audit mode until the number of unexpected audit events is minimal and acceptable.[9, 17, 20] A best practice involves building a “golden” reference machine with all necessary business applications installed to facilitate the generation of initial policies and the testing of refinements.[5, 27]

Transitioning from Audit to Enforced Mode

Once the audit logs demonstrate that the policy is stable and only blocking truly unwanted applications, the WDAC policy can be transitioned to “Enforced” mode.[9, 16, 17, 26, 27, 28]

-

- Caution: It is imperative to ensure that the enforced policy precisely aligns with the audit mode policy that was thoroughly validated.[26] Discrepancies or mixing of policies can lead to unexpected and disruptive blocks.[26]

-

- Phased Rollout: Even when moving to enforced mode, a phased rollout to larger groups of devices is advisable, beginning with a small, controlled group to mitigate risks.[19, 31, 32]

-

- Ongoing Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of WDAC events remains critical even in enforced mode. This allows for the identification of new applications or changes that might necessitate further policy updates.[9, 19]

The “audit first” recommendation is not merely a technical best practice; it is a critical business continuity strategy for SMBs.[17, 19, 20] An incorrectly enforced WDAC policy can halt operations, leading to significant financial losses and reputational damage. Audit mode functions as a safety net, enabling the pre-emptive identification and resolution of conflicts. This emphasizes that the time invested in the audit and refinement phase is an investment in operational stability. SMBs should allocate sufficient time for this phase, prioritizing it over rapid deployment, even if it appears to slow down the initial process. The ability to “fail fast” in audit mode prevents “failing hard” in production.

While the core WDAC functionality is available with Microsoft 365 Business Premium, Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE) Plan 2 offers “Advanced Hunting” capabilities for centralized monitoring of App Control events using KQL.[9, 19, 26] Microsoft 365 Business Premium includes Microsoft Defender for Business, which provides some MDE capabilities.[21] If an SMB has upgraded to Microsoft 365 E5 Security (which includes MDE Plan 2) or has Defender for Business, they can leverage these advanced hunting capabilities for more efficient and scalable audit log analysis. This provides a more robust and integrated security operations experience, even for smaller teams, enabling proactive threat hunting and policy refinement based on rich telemetry. Even without MDE Plan 2, the Azure Monitor agent and Log Analytics provide a strong centralized logging solution.[20]

Enhancing Security with Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) Rules

Beyond controlling which applications are permitted to run, a comprehensive security strategy must also address the behaviors of applications. Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) rules provide this crucial complementary layer of defense, working synergistically with WDAC.

How ASR Rules Complement WDAC for Layered Defense

WDAC focuses on what applications are allowed to run, operating on a whitelisting principle to ensure only approved code executes.[12, 33] In contrast, ASR rules, which are a component of Microsoft Defender for Endpoint, target behaviors commonly exploited by malware, irrespective of an application’s whitelisted status.[29, 33] These rules constrain risky software behaviors, such as:

-

- Launching executable files and scripts that attempt to download or run other files.

-

- Executing obfuscated or otherwise suspicious scripts.

-

- Performing actions that applications do not typically initiate during normal day-to-day operations.[29]

The synergy between WDAC and ASR rules is powerful: WDAC prevents unauthorized applications from running altogether, while ASR rules provide an additional layer of defense by blocking malicious actions even from legitimate, whitelisted applications that might be exploited.[6, 12, 33] This dual approach creates a robust, layered security posture [6, 12] and aligns with a Zero Trust strategy by continuously verifying and controlling processes and behaviors.[11, 12]

Configuring ASR Rules in Intune

Deploying ASR rules is managed through Microsoft Intune and requires specific prerequisites.

-

- Prerequisites: Devices must be enrolled in Microsoft Defender.[32] Microsoft Defender Antivirus must be configured as the primary antivirus solution, with real-time protection and Cloud-Delivery Protection enabled.[34] Microsoft 365 Business Premium includes Microsoft Defender for Business, which provides these essential capabilities.[21]

Step-by-Step Instructions:

-

- Open the Microsoft Intune admin center at https://intune.microsoft.com.

- Navigate to Endpoint security > Attack surface reduction.

- Click Create Policy.

- For Platform, select Windows 10, Windows 11, and Windows Server.

- For Profile, select Attack surface reduction rules.

- Click Create.

- In the Basics tab, enter a descriptive Name (e.g., “SMB ASR Rules – Audit Mode”) and an optional Description.[31]

- On the Configuration settings tab, under Attack Surface Reduction Rules, set all rules to Audit mode initially.[31, 32] This allows for monitoring and identification of false positives before any blocking occurs.[29, 32]

-

- Note: Some ASR rules may present “Blocked” and “Enabled” as modes, which function identically to “Block” and “Audit” respectively.[31] Other available modes include “Warn” (allowing user bypass) and “Disable”.[34]

-

- (Optional) Add Scope tags if applicable for managing access and visibility in distributed IT environments.[31]

-

- On the Assignments tab, assign the profile to a security group containing your target devices.[31] It is advisable to begin with a small pilot group for initial testing.

-

- Review the settings on the Review + create tab, then click Create to deploy the policy.

Table 4: Common ASR Rules and Recommended Modes for SMBs

| ASR Rule Name |

Description |

Recommended Mode for SMBs (Initial) |

Significance for SMBs |

| Block Adobe Reader from creating child processes |

Prevents Adobe Reader from launching executable child processes. |

Audit |

Mitigates common phishing vectors where malicious executables are launched from PDF documents. |

| Block all Office applications from creating child processes |

Prevents Office apps (Word, Excel, PowerPoint) from launching executable child processes. |

Audit |

Protects against macro-based malware and exploits that use Office applications to drop and execute payloads. |

| Block credential stealing from the Windows local security authority subsystem |

Prevents access to credentials stored in the Local Security Authority (LSA). |

Audit |

Protects critical user credentials from being harvested by attackers, preventing lateral movement. |

| Block execution of potentially obfuscated scripts |

Blocks scripts (e.g., PowerShell, VBScript) that are obfuscated or otherwise suspicious. |

Audit |

Mitigates script-based attacks, including fileless malware, which often use obfuscation to evade detection. |

| Block JavaScript or VBScript from launching downloaded executable content |

Prevents scripts from launching executables downloaded from the internet. |

Audit |

Addresses a common attack vector where malicious scripts initiate the download and execution of malware. |

Managing ASR Exclusions and Monitoring

Just as with WDAC, ASR rules may occasionally block legitimate applications or processes. To maintain operational continuity, exclusions can be configured for specific files or paths.[31, 34]

-

- Configuring Exclusions: In Intune, navigate to the ASR policy, select Properties, then Settings. Under “Exclude files and paths from attack surface reduction rules,” administrators can enter individual file paths or import a CSV file containing multiple exclusions.[34] Exclusions become active when the excluded application or service starts.[34]

-

- Monitoring:

-

- Microsoft Defender Portal: The Microsoft Defender portal provides detailed reports on detected activities, allowing administrators to track the effectiveness of ASR rules. Alerts are generated when rules are triggered, providing immediate visibility into potential threats.[29, 32]

-

- Windows Event Log: Administrators can review the Windows Event Log, specifically filtering for Event ID 1121 in the

Microsoft-Windows-Windows Defender/Operational log, to identify applications that would have been blocked by ASR rules.[29, 31]

Advanced Hunting (MDE Plan 2): For organizations with Microsoft Defender for Endpoint Plan 2, Kusto Query Language (KQL) can be used for advanced hunting to query ASR events (e.g., DeviceEvents | where ActionType startswith 'Asr').[29] This capability offers deep insights for policy refinement.

-

- Refinement: Continuous monitoring of audit logs, identification of false positives, addition of necessary exclusions, and gradual transition of ASR rules from audit to block mode are essential for optimal security and operational efficiency.[29, 32]

WDAC focuses on the identity of what is allowed to run, while ASR focuses on the behavior of applications.[33] This distinction means that even if a legitimate, whitelisted application is compromised (e.g., through a malicious macro or an exploited vulnerability), ASR rules can still prevent suspicious behavior that WDAC alone might not detect. This highlights the “layered security” aspect, where WDAC establishes a strong perimeter, and ASR acts as an internal tripwire [32], catching threats that bypass initial application control. This dual approach significantly enhances resilience against sophisticated attacks like fileless malware and zero-day exploits [6], which are increasingly targeting SMBs.

Like WDAC, ASR rules can cause operational disruptions if not properly configured.[32] Microsoft consistently recommends starting with “Audit” mode and testing with a small, controlled group.[29, 31, 32] User notifications can also appear when ASR blocks content.[29] For SMBs, a phased rollout and transparent communication with users are crucial. Starting with audit mode allows IT to identify legitimate business processes that trigger ASR rules. Customizing user notifications [29] can reduce help desk calls and improve user understanding and acceptance of new security measures. This proactive communication helps manage user expectations and ensures a smoother transition to enforced security.

Layered Security for SMBs with Microsoft 365 Business Premium

Achieving a robust security posture for SMBs requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates various security controls. The combination of WDAC and ASR rules within the Microsoft 365 Business Premium ecosystem provides a powerful, layered defense.

Integrating WDAC and ASR for a Robust Endpoint Security Posture

The synergistic combination of WDAC (application whitelisting) and ASR rules (behavioral control) establishes a powerful, multi-layered defense against a wide spectrum of cyber threats, including ransomware, zero-day exploits, and fileless malware.[6, 12] WDAC functions as the primary gatekeeper, ensuring that only trusted and approved code is permitted to execute. Concurrently, ASR rules provide a crucial secondary defense by detecting and blocking suspicious activities, even when originating from legitimate, whitelisted applications that might have been compromised.[33] This integrated approach significantly reduces the overall attack surface on Windows endpoints, minimizing opportunities for malicious actors to gain a foothold.[6, 29]

Leveraging Microsoft Defender for Business Capabilities

Microsoft 365 Business Premium is designed as a comprehensive productivity and security solution for SMBs, encompassing essential tools for modern endpoint protection.[21, 22] This subscription includes Microsoft Intune Plan 1 for endpoint management, security, and mobile application management, as well as Microsoft Defender for Business for device protection.[21] This suite provides the foundational capabilities necessary for centrally deploying and managing both WDAC and ASR policies via Intune.[6, 10, 16, 21, 31, 34] For SMBs seeking even more advanced security capabilities, an upgrade to Microsoft 365 E5 Security is available. This add-on includes Microsoft Defender for Endpoint Plan 2, which offers enhanced threat hunting, live response capabilities, and more extensive data retention for deeper security insights.[21, 29]

Microsoft 365 Business Premium bundles Intune and Defender for Business [21, 22], providing the core tools for implementing advanced application control (WDAC and ASR) without requiring additional, often expensive, third-party solutions. This aligns with the SMB imperative for managing security within limited budgets.[11] The integrated management through Intune simplifies both initial deployment and ongoing operations, which is critical for smaller IT teams. This offers a strong security baseline, extending protection “from the chip to the cloud” for SMBs.[11]

Practical Considerations for Ongoing Management and Maintenance in SMBs

Application control, particularly with WDAC, is not a “set-and-forget” solution.[5] It requires continuous attention to remain effective.

-

- Continuous Monitoring: Regular monitoring of audit logs (via local Event Viewer or centralized Azure Monitor/Log Analytics) is essential to identify new legitimate applications or changes in existing ones that necessitate policy updates.[9, 19, 20]

-

- Policy Updates: Organizations must be prepared to update WDAC and ASR policies as new software is introduced, existing software is updated, or business processes evolve.[5, 7, 8] Maintaining clear documentation of policy rules and exceptions is crucial for efficient management.

-

- Resource Allocation: While WDAC and ASR significantly enhance security, they demand an initial investment of time for planning, testing, and refinement.[5, 7, 8, 17] SMBs should factor this into their IT planning and resource allocation.

-

- User Education: Educating end-users about the purpose of application control and providing clear channels for reporting issues when legitimate applications are blocked can significantly reduce help desk tickets and improve user acceptance of new security measures.[7]

-

- Least Privilege: The principle of least privilege for user accounts should continue to be applied. Even with robust application control, limiting user permissions adds an additional layer of defense against potential compromises.[13]

-

- Hybrid Approach: In certain scenarios, a hybrid approach might be beneficial, where AppLocker is used for granular user- or group-specific rules on shared devices, complementing the device-wide WDAC policies.[2, 5]

-

- Backup and Recovery: It is imperative to ensure robust backup and recovery procedures are in place. While application control prevents unauthorized execution, it does not negate the fundamental need for comprehensive data protection against other forms of data loss or corruption.

The repeated emphasis in the research that WDAC is not a “set-and-forget” solution and requires ongoing maintenance and refinement [5, 7, 8] highlights the dynamic nature of both software environments and the threat landscape. Policies can become outdated quickly.[5] For SMBs, while the initial setup is a significant undertaking, the long-term success of application control depends on a commitment to continuous monitoring and policy adaptation. SMBs should establish a regular review cadence for their policies and leverage audit mode for testing any changes. This ensures their security posture remains effective against evolving threats and adapts to changing business needs. This also implies the potential need for developing internal expertise or engaging a trusted IT partner for ongoing management.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The journey from basic application blocking to a comprehensive, proactive security posture for Windows devices with Microsoft 365 Business Premium involves a strategic shift from rudimentary AppLocker implementations to advanced Windows Defender Application Control (WDAC) and Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) rules. This report has detailed how WDAC, operating on a whitelisting principle, acts as a primary gatekeeper for application execution, while ASR rules provide a crucial behavioral safety net, together forming a robust, layered defense against a wide spectrum of cyber threats, including zero-day exploits and ransomware. The integrated management capabilities within Microsoft Intune, part of Microsoft 365 Business Premium, provide the necessary tools for SMBs to deploy and manage these sophisticated controls.

Actionable Next Steps for SMBs:

To implement this comprehensive application prevention strategy, SMBs should consider the following actionable steps:

-

- Assess Current Environment: Conduct a thorough inventory of existing applications and identify all critical business software essential for daily operations. This forms the basis for whitelist creation.

- Enable Managed Installer: Configure the Intune Management Extension as a managed installer within the Microsoft Intune admin center. This action automates the trust for applications deployed via Intune, significantly reducing manual whitelisting efforts for future software deployments.

- Start with WDAC in Audit Mode: Utilize the WDAC Wizard to create a base policy, such as the “Signed and Reputable Mode” template. Deploy this policy in audit mode to a small, controlled pilot group of devices. This crucial step allows for testing and identification of legitimate applications that might otherwise be blocked, without disrupting operations.

- Implement Centralized Logging: Set up Azure Monitor with a Log Analytics Workspace to collect WDAC audit events. This centralized logging solution facilitates efficient analysis of audit data using Kusto Query Language (KQL), providing a scalable approach to policy refinement.

- Iterative Refinement: Continuously monitor the collected audit logs, identify any legitimate applications that are being flagged for blocking, and use the WDAC Wizard to create supplemental policies or update the base policy to explicitly allow them. Redeploy the updated policies in audit mode to the pilot group and repeat this cycle until the number of unexpected audit events is minimal and acceptable.

- Transition to Enforced Mode (Phased): Once the audit logs confirm policy stability and effectiveness, gradually roll out WDAC policies in enforced mode. Begin with low-impact groups and expand systematically, ensuring the enforced policy precisely matches the validated audit mode policy.

- Configure ASR Rules in Audit Mode: Deploy Attack Surface Reduction rules via Intune, initially setting all rules to audit mode. This allows for monitoring of potential false positives and understanding their impact on your environment before enforcement.

- Refine and Enforce ASR Rules: Based on audit log analysis, configure necessary exclusions for ASR rules and gradually transition them to block mode. Continuously monitor the Microsoft Defender portal and Event Logs for triggered ASR events.

- Maintain and Monitor: Establish ongoing processes for continuous monitoring of both WDAC and ASR events. Regularly review and update policies as new software is introduced, existing applications are updated, or business processes evolve. Application control is an ongoing commitment, not a one-time configuration.

- Leverage Microsoft Defender: Ensure Microsoft Defender for Business, included with Microsoft 365 Business Premium, is fully utilized for its antivirus capabilities, real-time protection, and cloud-delivery protection. For organizations seeking deeper security insights and advanced threat hunting, consider the Microsoft 365 E5 Security add-on, which includes Microsoft Defender for Endpoint Plan 2.