Copilot Studio is Microsoft’s low-code platform for building AI-powered agents (custom “Copilots”) that extend Microsoft 365 Copilot’s capabilities[1]. These agents are specialized assistants with defined roles, tools, and knowledge, designed to help users with specific tasks or domains. A central element in building a successful agent is its instructions field – the set of written guidelines that define the agent’s behavior, capabilities, and boundaries. Getting this instructions field correct is absolutely critical for the agent to operate as designed.

In this report, we explain why well-crafted instructions are vital, illustrate good vs. bad instruction examples (and why they succeed or fail), and provide a detailed framework and best practices for writing effective instructions in Copilot Studio. We also cover how to test and refine instructions, accommodate different types of agents, and leverage resources to continuously improve your agent instructions.

Overview: Copilot Studio and the Instructions Field

What is Copilot Studio? Copilot Studio is a user-friendly environment (part of Microsoft Power Platform) that enables creators to build and deploy custom Copilot agents without extensive coding[1]. These agents leverage large language models (LLMs) and your configured tools/knowledge to assist users, but they are more scoped and specialized than the general-purpose Microsoft 365 Copilot[2]. For example, you could create an “IT Support Copilot” that helps employees troubleshoot tech issues, or a “Policy Copilot” that answers HR policy questions. Copilot Studio supports different agent types – commonly conversational agents (interactive chatbots that users converse with) and trigger/action agents (which run workflows or tasks based on triggers).

Role of the Instructions Field: Within Copilot Studio, the instructions field is where you define the agent’s guiding principles and behavior rules. Instructions are the central directions and parameters the agent follows[3]. In practice, this field serves as the agent’s “system prompt” or policy:

- It establishes the agent’s identity, role, and purpose (what the agent is supposed to do and not do)[1].

- It defines the agent’s capabilities and scope, referencing what tools or data sources to use (and in what situations)[3].

- It sets the desired tone, style, and format of the agent’s responses (for consistent user experience).

- It can include step-by-step workflows or decision logic the agent should follow for certain tasks[4].

- It may impose restrictions or safety rules, such as avoiding certain content or escalating issues per policy[1].

In short, the instructions tell the agent how to behave and how to think when handling user queries or performing its automated tasks. Every time the agent receives a user input (or a trigger fires), the underlying AI references these instructions to decide:

- What actions to take – e.g. which tool or knowledge base to consult, based on what the instructions emphasize[3].

- How to execute those actions – e.g. filling in tool inputs with user context as instructed[3].

- How to formulate the final answer – e.g. style guidelines, level of detail, format (bullet list, table, etc.), as specified in the instructions.

Because the agent’s reasoning is grounded in the instructions, those instructions need to be accurate, clear, and aligned with the agent’s intended design. An agent cannot obey instructions to use tools or data it doesn’t have access to; thus, instructions must also stay within the bounds of the agent’s configured tools/knowledge[3].

Why Getting the Instructions Right is Critical

Writing the instructions field correctly is critical because it directly determines whether your agent will operate as intended. If the instructions are poorly written or wrong, the agent will likely deviate from the desired behavior. Here are key reasons why correct instructions are so important:

- They are the Foundation of Agent Behavior: The instructions form the foundation or “brain” of your agent. Microsoft’s guidance notes that agent instructions “serve as the foundation for agent behavior, defining personality, capabilities, and operational parameters.”[1]. A well-formulated instructions set essentially hardcodes your agent’s expertise (what it knows), its role (what it should do), and its style (how it interacts). If this foundation is shaky, the agent’s behavior will be unpredictable or ineffective.

- Ensuring Relevant and Accurate Responses: Copilot agents rely on instructions to produce responses that are relevant, accurate, and contextually appropriate to user queries[5]. Good instructions tell the agent exactly how to use your configured knowledge sources and when to invoke specific actions. Without clear guidance, the AI might rely on generic model knowledge or make incorrect assumptions, leading to hallucinations (made-up info) or off-target answers. In contrast, precise instructions keep the agent’s answers on track and grounded in the right information.

- Driving the Correct Use of Tools/Knowledge: In Copilot Studio, agents can be given “skills” (API plugins, enterprise data connectors, etc.). The instructions essentially orchestrate these skills. They might say, for example, “If the user asks about an IT issue, use the IT Knowledge Base search tool,” or “When needing current data, call the WebSearch capability.” If these directions aren’t specified or are misspecified, the agent may not utilize the tools correctly (or at all). The instructions are how you, the creator, impart logic to the agent’s decision-making about tools and data. Microsoft documentation emphasizes that agents depend on instructions to figure out which tool or knowledge source to call and how to fill in its inputs[3]. So, getting this right is essential for the agent to actually leverage its configured capabilities in solving user requests.

- Maintaining Consistency and Compliance: A Copilot agent often needs to follow particular tone or policy rules (e.g., privacy guidelines, company policy compliance). The instructions field is where you encode these. For instance, you can instruct the agent to always use a polite tone, or to only provide answers based on certain trusted data sources. If these rules are not clearly stated, the agent might inadvertently produce responses that violate style expectations or compliance requirements. For example, if an agent should never answer medical questions beyond a provided medical knowledge base, the instructions must say so explicitly; otherwise the agent might try to answer from general training data – a big risk in regulated scenarios. In short, correct instructions protect against undesirable outputs by outlining do’s and don’ts (though as a rule of thumb, phrasing instructions in terms of positive actions is preferred – more on that later).

- Optimal User Experience: Finally, the quality of the instructions directly translates to the quality of the user’s experience with the agent. With well-crafted instructions, the agent will ask the right clarifying questions, present information in a helpful format, and handle edge cases gracefully – all of which lead to higher user satisfaction. Conversely, bad instructions can cause an agent to be confusing, unhelpful, or even completely off-base. Users may get frustrated if the agent requires too much guidance (because the instructions didn’t prepare it well), or if the agent’s responses are messy or incorrect. Essentially, instructions are how you design the user’s interaction with your agent. As one expert succinctly put it, clear instructions ensure the AI understands the user’s intent and delivers the desired output[5] – which is exactly what users want.

Bottom line: If the instructions field is right, the agent will largely behave and perform as designed – using the correct data, following the intended workflow, and speaking in the intended voice. If the instructions are wrong or incomplete, the agent’s behavior can diverge, leading to mistakes or an experience that doesn’t meet your goals. Now, let’s explore what good instructions look like versus bad instructions, to illustrate these points in practice.

Good vs. Bad Instructions: Examples and Analysis

Writing effective agent instructions is somewhat of an art and science. To understand the difference it makes, consider the following examples of a good instruction set versus a bad instruction set for an agent. We’ll then analyze why the good one works well and why the bad one falls short.

Example of Good Instructions

Imagine we are creating an IT Support Agent that helps employees with common technical issues. A good instructions set for such an agent might look like this (simplified excerpt):

You are an IT support specialist focused on helping employees with common technical issues. You have access to the company’s IT knowledge base and troubleshooting guides.\ Your responsibilities include:\ – Providing step-by-step troubleshooting assistance.\ – Escalating complex issues to the IT helpdesk when necessary.\ – Maintaining a helpful and patient demeanor.\ – Ensuring solutions follow company security policies.\ When responding to requests:

- Ask clarifying questions to understand the issue.

- Provide clear, actionable solutions or instructions.

- Verify whether the solution worked for the user.

- If resolved, summarize the fix; if not, consider escalation or next steps.[1]

This is an example of well-crafted instructions. Notice several positive qualities:

- Clear role and scope: It explicitly states the agent’s role (“IT support specialist”) and what it should do (help with tech issues using company knowledge)[1]. The agent’s domain and expertise are well-defined.

- Specific responsibilities and guidelines: It lists responsibilities and constraints (step-by-step help, escalate if needed, be patient, follow security policy) in bullet form. This acts as general guidelines for behavior and ensures the agent adheres to important policies (like security rules)[1].

- Actionable step-by-step approach: Under responding to requests, it breaks down the procedure into an ordered list of steps: ask clarifying questions, then give solutions, then verify, etc.[1]. This provides a clear workflow for the agent to follow on each query. Each step has a concrete action, reducing ambiguity.

- Positive/constructive tone: The instructions focus on what the agent should do (“ask…”, “provide…”, “verify…”) rather than just what to avoid. This aligns with best practices that emphasize guiding the AI with affirmative actions[4]. (If there are things to avoid, they could be stated too, but in this example the necessary restrictions – like sticking to company guides and policies – are inherently covered.)

- Aligned with configured capabilities: The instructions mention the knowledge base and troubleshooting guides, which presumably are set up as the agent’s connected data. Thus, the agent is directed to use available resources. (A good instruction set doesn’t tell the agent to do impossible things; here it wouldn’t, say, ask the agent to remote-control a PC unless such an action plugin exists.)

Overall, these instructions would likely lead the agent to behave helpfully and stay within bounds. It’s clear what the agent should do and how.

Example of Bad Instructions

Now consider a contrasting example. Suppose we tried to instruct the same kind of agent with this single instruction line:

“You are an agent that can help the user.”

This is obviously too vague and minimal, but it illustrates a “bad” instructions scenario. The agent is given virtually no guidance except a generic role. There are many issues here:

- No clarification of domain or scope (help the user with what? anything?).

- No detail on which resources or tools to use.

- No workflow or process for handling queries.

- No guidance on style, tone, or policy constraints. Such an agent would be flying blind. It might respond generically to any question, possibly hallucinate answers because it’s not instructed to stick to a knowledge base, and would not follow a consistent multi-step approach to problems. If a user asked it a technical question, the agent might not know to consult the IT knowledge base (since we never told it to). The result would be inconsistent and likely unsatisfactory.

Bad instructions can also occur in less obvious ways. Often, instructions are “bad” not because they are too short, but because they are unclear, overly complicated, or misaligned. For example, consider this more detailed but flawed instruction example (adapted from an official guidance of what not to do):

“If a user asks about coffee shops, focus on promoting Contoso Coffee in US locations, and list those shops in alphabetical order. Format the response as a series of steps, starting each step with Step 1:, Step 2: in bold. Don’t use a numbered list.”[6]

At first glance it’s detailed, but this is labeled as a weak instruction by Microsoft’s documentation. Why is this considered a bad/weak set of instructions?

- It mixes multiple directives in one blob: It tells the agent what content to prioritize (Contoso Coffee in US) and prescribes a very specific formatting style (steps with “Step 1:”, but strangely “don’t use a numbered list” simultaneously). This could confuse the model or yield rigid responses. Good instructions would separate concerns (perhaps have a formatting rule separately and a content preference rule separately).

- It’s too narrow and conditional: “If a user asks about coffee shops…” – what if the user asks something slightly different? The instruction is tied to a specific scenario, rather than a general principle. This reduces the agent’s flexibility or could even be ignored if the query doesn’t exactly match.

- The presence of a negative directive (“Don’t use a numbered list”) could be stated in a clearer positive way. In general, saying what not to do is sometimes necessary, but overemphasizing negatives can lead the model to fixate incorrectly. (A better version might have been: “Format the list as bullet points rather than a numbered list.”)

In summary, bad instructions are those that lack clarity, completeness, or coherence. They might be too vague (leaving the AI to guess what you intended) or too convoluted/conditional (making it hard for the AI to parse the main intent). Bad instructions can also contradict the agent’s configuration (e.g., telling it to use a data source it doesn’t have) – such instructions will simply be ignored by the agent[3] but they waste precious prompt space and can confuse the model’s reasoning. Another failure mode is focusing only on what not to do without guiding what to do. For instance, an instructions set that says a lot of “Don’t do X, avoid Y, never say Z” and little else, may constrain the agent but not tell it how to succeed – the agent might then either do nothing useful or inadvertently do something outside the unmentioned bounds.

Why the Good Example Succeeds (and the Bad Fails):\ The good instructions provide specificity and structure – the agent knows its role, has a procedure to follow, and boundaries to respect. This reduces ambiguity and aligns with how the Copilot engine decides on actions and outputs[3]. The bad instructions give either no direction or confusing direction, which means the model might revert to its generic training (not your custom data) or produce unpredictable outputs. In essence:

- Good instructions guide the agent step-by-step to fulfill its purpose, covering various scenarios (normal case, if issue unclear, if issue resolved or needs escalation, etc.).

- Bad instructions leave gaps or introduce confusion, so the agent may not behave consistently with the designer’s intent.

Next, we’ll delve into common pitfalls to avoid when writing instructions, and then outline best practices and a framework to craft instructions akin to the “good” example above.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid in Agent Instructions

When designing your agent’s instructions field in Copilot Studio, be mindful to avoid these frequent pitfalls:

1. Being Too Vague or Brief: As shown in the bad example, overly minimal instructions (e.g. one-liners like “You are a helpful agent”) do not set your agent up for success. Ambiguity in instructions forces the AI to guess your intentions, often leading to irrelevant or inconsistent behavior. Always provide enough context and detail so that the agent doesn’t have to “infer” what you likely want – spell it out.

2. Overwhelming with Irrelevant Details: The opposite of being vague is packing the instructions with extraneous or scenario-specific detail that isn’t generally applicable. For instance, hardcoding a very specific response format for one narrow case (like the coffee shop example) can actually reduce the agent’s flexibility for other cases. Avoid overly verbose instructions that might distract or confuse the model; keep them focused on the general patterns of behavior you want.

3. Contradictory or Confusing Rules: Ensure your instructions don’t conflict with themselves. Telling the agent “be concise” in one line and then later “provide as much detail as possible” is a recipe for confusion. Similarly, avoid mixing positive and negative instructions that conflict (e.g. “List steps as Step 1, Step 2… but don’t number them” from the bad example). If the logic or formatting guidance is complex, clarify it with examples or break it into simpler rules. Consistency in your directives will lead to consistent agent responses.

4. Focusing on Don’ts Without Do’s: As a best practice, try to phrase instructions proactively (“Do X”) rather than just prohibitions (“Don’t do Y”)[4]. Listing many “don’ts” can box the agent in or lead to odd phrasings as it contorts to avoid forbidden words. It’s often more effective to tell the agent what it should do instead. For example, instead of only saying “Don’t use a casual tone,” a better instruction is “Use a formal, professional tone.” That said, if there are hard no-go areas (like “do not provide medical advice beyond the provided guidelines”), you should include them – just make sure you’ve also told the agent how to handle those cases (e.g., “if asked medical questions outside the guidelines, politely refuse and refer to a doctor”).

5. Not Covering Error Handling or Unknowns: A common oversight is failing to instruct the agent on what to do if it doesn’t have an answer or if a tool returns no result. If not guided, the AI might hallucinate an answer when it actually doesn’t know. Mitigate this by adding instructions like: “If you cannot find the answer in the knowledge base, admit that and ask the user if they want to escalate.” This kind of error handling guidance prevents the agent from stalling or giving false answers[4]. Similarly, if the agent uses tools, instruct it about when to call them and when not to – e.g. “Only call the database search if the query contains a product name” to avoid pointless tool calls[4].

6. Ignoring the Agent’s Configured Scope: Sometimes writers accidentally instruct the agent beyond its capabilities. For example, telling an agent “search the web for latest news” when the agent doesn’t have a web search skill configured. The agent will simply not do that (it can’t), and your instruction is wasted. Always align instructions with the actual skills/knowledge sources configured for the agent[3]. If you update the agent to add new data sources or actions, update the instructions to incorporate them as well.

7. No Iteration or Testing: Treating the first draft of instructions as final is a mistake (we expand on this later). It’s a pitfall to assume you’ve written the perfect prompt on the first try. In reality, you’ll likely discover gaps or ambiguities when you test the agent. Not iterating is a pitfall in itself – it leads to suboptimal agents. Avoid this by planning for multiple refine-and-test cycles.

By being aware of these pitfalls, you can double-check your instructions draft and revise it to dodge these common errors. Now let’s focus on what to do: the best practices and a structured framework for writing high-quality instructions.

Best Practices for Writing Effective Instructions

Writing great instructions for Copilot Studio agents requires clarity, structure, and an understanding of how the AI interprets your prompts. Below are established best practices, gathered from Microsoft’s guidance and successful agent designers:

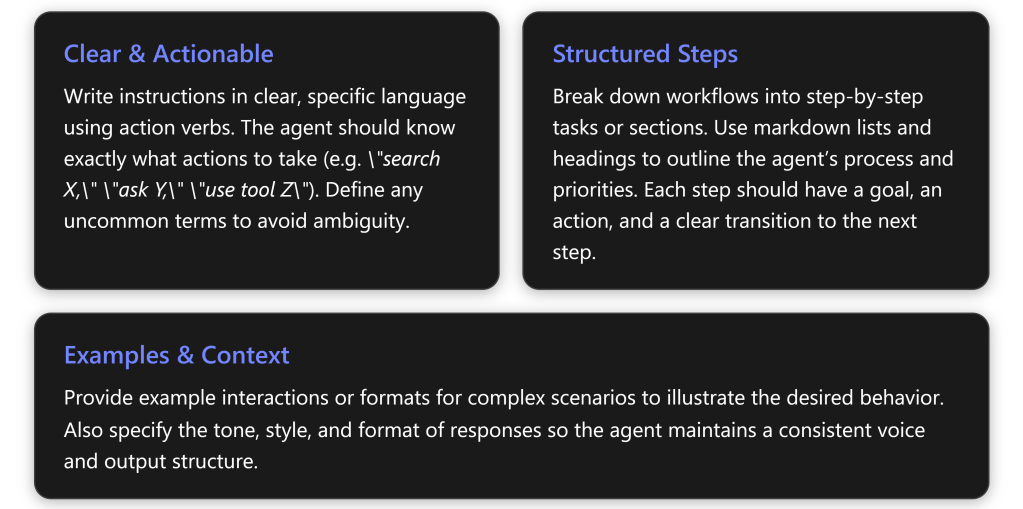

- Use Clear, Actionable Language: Write instructions in straightforward terms and use specific action verbs. The agent should immediately grasp what action is expected. Microsoft recommends using precise verbs like “ask,” “search,” “send,” “check,” or “use” when telling the agent what to do[4]. For example, “Search the HR policy database for any mention of parental leave,” is much clearer than “Find info about leave” – the former explicitly tells the agent which resource to use and what to look for. Avoid ambiguity: if your organization uses unique terminology or acronyms, define them in the instructions so the AI knows what they mean[4].

- Focus on What the Agent Should Do (Positive Instructions): As noted, frame rules in terms of desirable actions whenever possible[4]. E.g., say “Provide a brief summary followed by two recommendations,” instead of “Do not ramble or give too many options.” Positive phrasing guides the model along the happy path. Include necessary restrictions (compliance, safety) but balance them by telling the agent how to succeed within those restrictions.

- Provide a Structured Template or Workflow: It often helps to break the agent’s task into step-by-step instructions or sections. This could mean outlining the conversation flow in steps (Step 1, Step 2, etc.) or dividing the instructions into logical sections (like “Objective,” “Response Guidelines,” “Workflow Steps,” “Closing”)[4]. Using Markdown formatting (headers, numbered lists, bullet points) in the instructions field is supported, and it can improve clarity for the AI[4]. For instance, you might have:

- A Purpose section: describing the agent’s goal and overall approach.

- Rules/Guidelines: bullet points for style and policy (like the do’s and don’ts).

- A stepwise Workflow: if the agent needs to go through a sequence of actions (as we did in the IT support example with steps 1-4).

- Perhaps Error Handling instructions: what to do if things go wrong or info is missing.

- Example interactions (see below). This structured approach helps the model follow your intended order of operations. Each step should be unambiguous and ideally say when to move to the next step (a “transition” condition)[4]. For example, “Step 1: Do X… (if outcome is Y, then proceed to Step 2; if not, respond with Z and end).”

- Highlight Key Entities and Terms: If your agent will use particular tools or reference specific data sources, call them out clearly by name in the instructions. For example: “Use the

<ToolName>action to retrieve inventory data,” or “Consult the PolicyWiki knowledge base for policy questions.” By naming the tool/knowledge, you help the AI choose the correct resource at runtime. In technical terms, the agent matches your words with the names/descriptions of the tools and data sources you attached[3]. So if your knowledge base is called “Contoso FAQ”, instruct “search the Contoso FAQ for relevant answers” – this makes a direct connection. Microsoft’s best practices suggest explicitly referencing capabilities or data sources involved at each step[4]. Also, if your instructions mention any uncommon jargon, define it so the AI doesn’t misunderstand (e.g., “Note: ‘HCS’ refers to the Health & Care Service platform in our context” as seen in a sample[1]). - Set the Tone and Style: Don’t forget to tell your agent how to talk to the user. Is the tone friendly and casual, or formal and professional? Should answers be brief or very detailed? State these as guidelines. For example: “Maintain a conversational and encouraging tone, using simple language” or “Respond in a formal style suitable for executive communications.” If formatting is important (like always giving answers in a table or starting with a summary bullet list), include that instruction. E.g., “Present the output as a table with columns X, Y, Z,” or “Whenever listing items, use bullet points for readability.” In our earlier IT agent example, instructions included “provide clear, concise explanations” as a response approach[1]. Such guidance ensures consistency in output regardless of which AI model iteration is behind the scenes.

- Incorporate Examples (Few-Shot Prompting): For complex agents or those handling nuanced tasks, providing example dialogs or cases in the instructions can significantly improve performance. This technique is known as few-shot prompting. Essentially, you append one or more example interactions (a sample user query and how the agent should respond) in the instructions. This helps the AI understand the pattern or style you expect. Microsoft suggests using examples especially for complex scenarios or edge cases[4]. For instance, if building a legal Q\&A agent, you might give an example Q\&A where the user asks a legal question and the agent responds citing a specific policy clause, to show the desired behavior. Be careful not to include too many examples (which can eat up token space) – use representative ones. In practice, even 1–3 well-chosen examples can guide the model. If your agent requires multi-turn conversational ability (asking clarifying questions, etc.), you might include a short dialogue example illustrating that flow[7][7]. Examples make instructions much more concrete and minimize ambiguity about how to implement the rules.

- Anticipate and Prevent Common Failures: Based on known LLM behaviors, watch out for issues like:

- Over-eager tool usage: Sometimes the model might call a tool too early or without needed info. Solution: explicitly instruct conditions for tool use (e.g., “Only use the translation API if the user actually provided text to translate”)[4].

- Repetition: The model might parrot an example wording in its response. To counter this, encourage it to vary phrasing or provide multiple examples so it generalizes the pattern rather than copying verbatim[4].

- Over-verbosity: If you fear the agent will give overly long explanations, add a constraint like “Keep answers under 5 sentences when possible” or “Be concise and to-the-point.” Providing an example of a concise answer can reinforce this[4]. Many of these issues can be tuned by small tweaks in instructions. The key is to be aware of them and adjust wording accordingly. For example, to avoid verbose outputs, you might include a bullet: “Limit the response to the essential information; do not elaborate with unnecessary background.”

- Use Markdown for Emphasis and Clarity: We touched on structure with Markdown headings and lists. Additionally, you can use bold text in instructions to highlight critical rules the agent absolutely must not miss[4]. For instance: “Always confirm with the user before closing the session.” Using bold can give that rule extra weight in the AI’s processing. You can also put specific terms in backticks to indicate things like literal values or code (e.g., “set status to

Closedin the ticketing system”). These formatting touches help the AI distinguish instruction content from plain narrative.

Following these best practices will help you create a robust set of instructions. The next step is to approach the writing process systematically. We’ll introduce a simple framework to ensure you cover all bases when drafting instructions for a Copilot agent.

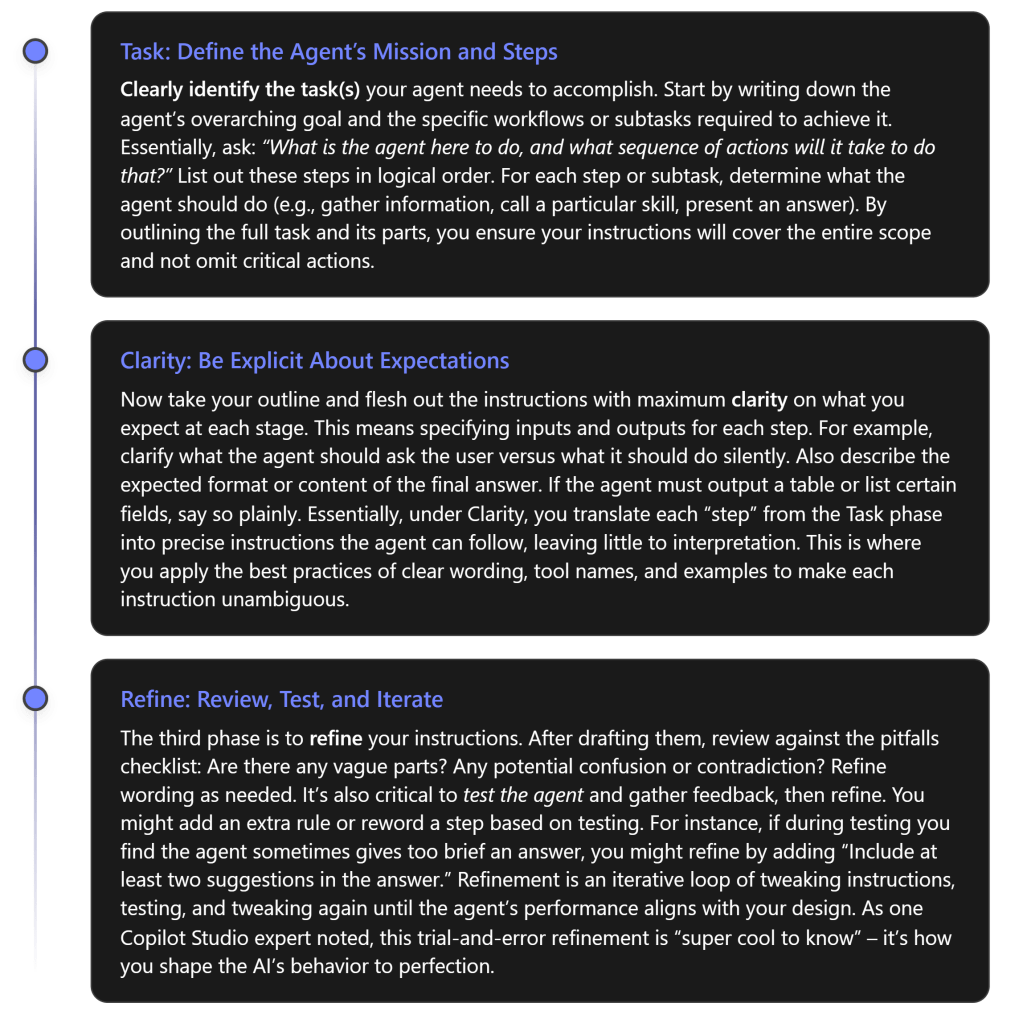

Framework for Crafting Agent Instructions (T-C-R Approach)

It can be helpful to follow a repeatable framework when drafting instructions for an agent. One useful approach is the T-C-R framework: Task – Clarity – Refine[5]:

Using this T-C-R framework ensures you tackle instruction-writing methodically:

- Task: You don’t forget any part of the agent’s job.

- Clarity: You articulate exactly what’s expected for each part.

- Refine: You catch issues and continuously improve the prompt.

It’s similar to how one might approach writing requirements for a software program – be thorough and clear, then test and revise.

Testing and Validation of Agent Instructions

Even the best-written first draft of instructions can behave unexpectedly when put into practice. Therefore, rigorous testing and validation is a crucial phase in developing Copilot Studio agents.

Use the Testing Tools: Copilot Studio provides a Test Panel where you can interact with your agent in real time, and for trigger-based agents, you can use test payloads or scenarios[3]. As soon as you write or edit instructions, test the agent with a variety of inputs:

- Start with simple, expected queries: Does the agent follow the steps? Does it call the intended tools (you might see this in logs or the response content)? Is the answer well-formatted?

- Then try edge cases or slightly off-beat inputs: If something is ambiguous or missing in the user’s question, does the agent ask the clarifying question as instructed? If the user asks something outside the agent’s scope, does it handle it gracefully (e.g., with a refusal or a redirect as per instructions)?

- If your agent has multiple distinct functionalities (say, it both can fetch data and also compose emails), test each function individually.

Validate Against Design Expectations: As you test, compare the agent’s actual behavior to the design you intended. This can be done by creating a checklist of expected behaviors drawn from your instructions. For example: “Did the agent greet the user? ✅”, “Did it avoid giving unsupported medical advice? ✅”, “When I asked a second follow-up question, did it remember context? ✅” etc. Microsoft suggests comparing the agent’s answers to a baseline, like Microsoft 365 Copilot’s answers, to see if your specialized agent is adding the value it should[4]. If your agent isn’t outperforming the generic copilot or isn’t following your rules, that’s a sign the instructions need tweaking or the agent needs additional knowledge.

RAI (Responsible AI) Validation: When you publish an agent, Microsoft 365’s platform will likely run some automated checks for responsible AI compliance (for instance, ensuring no obviously disallowed instructions are present)[4]. Usually, if you stick to professional content and the domain of your enterprise data, this won’t be an issue. But it’s good to double-check that your instructions themselves don’t violate any policies (e.g., telling the agent to do something unethical). This is part of validation – making sure your instructions are not only effective but also compliant.

Iterate Based on Results: It’s rare to get the instructions perfect on the first try. You might observe during testing that the agent does something odd or suboptimal. Use those observations to refine the instructions (this is the “Refine” step of the T-C-R framework). For example, if the agent’s answers are too verbose, you might add a line in instructions: “Be brief in your responses, focusing only on the solution.” Test again and see if that helped. Or if the agent didn’t use a tool when it should have, maybe you need to mention that tool by name more explicitly or adjust the phrasing that cues it. This experimental mindset – tweak, test, tweak, test – is essential. Microsoft’s documentation illustration for declarative agents shows an iterative loop of designing instructions, testing, and modifying instructions to improve outcomes[4][4].

Document Your Tests: As your instructions get more complex, it’s useful to maintain a set of test cases or scenarios with expected outcomes. Each time you refine instructions, run through your test cases to ensure nothing regressed and new changes work as intended. Over time, this becomes a regression test suite for your agent’s behavior.

By thoroughly testing and validating, you ensure the instructions truly yield an agent that operates as designed. Once initial testing is satisfactory, you can move to a pilot deployment or let some end-users try the agent, then gather their feedback – feeding into the next topic: improvement mechanisms.

Iteration and Feedback: Continuous Improvement of Instructions

An agent’s instructions are not a “write once, done forever” artifact. They should be viewed as living documentation that can evolve with user needs and as you discover what works best. Two key processes for continuous improvement are monitoring feedback and iterating instructions over time:

- Gather User Feedback: After deploying the agent to real users (or a test group), collect feedback on its performance. This can be direct feedback (users rating responses or reporting issues) or indirect, like observing usage logs. Pay attention to questions the agent fails to answer or any time users seem confused by the agent’s output. These are golden clues that the instructions might need adjustment. For example, if users keep asking for clarification on the agent’s answers, maybe your instructions should tell the agent to be more explanatory on first attempt. If users trigger the agent in scenarios it wasn’t originally designed for, you might decide to broaden the instructions (or explicitly handle those out-of-scope cases in the instructions with a polite refusal).

- Review Analytics and Logs: Copilot Studio (and related Power Platform tools) may provide analytics such as conversation transcripts, success rates of actions, etc. Microsoft advises to “regularly review your agent results and refine custom instructions based on desired outcomes.”[6]. For instance, if analytics show a particular tool call failing frequently, maybe the instructions need to better gate when that tool is used. Or if users drop off after the agent’s first answer, perhaps the agent is not engaging enough – you might tweak the tone or ask a question back in the instructions. Treat these data points as feedback for improvement.

- Incremental Refinements: Incorporate the feedback into improved instructions, and update the agent. Because Copilot Studio allows you to edit and republish instructions easily[3], you can make iterative changes even after deployment. Just like software updates, push instruction updates to fix “bugs” in agent behavior. Always test changes in a controlled way (in the studio test panel or with a small user group) before rolling out widely.

- Keep Iterating: The process of testing and refining is cyclical. Your agent can always get better as you discover new user requirements or corner cases. Microsoft’s guidance strongly encourages an iterative approach, as illustrated by their steps: create -> test -> verify -> modify -> test again[4][4]. Over time, these tweaks lead to a very polished set of instructions that anticipates many user needs and failure modes.

- Version Control Your Instructions: It’s good practice to keep track of changes (what was added, removed, or rephrased in each iteration). This way if a change unexpectedly worsens the agent’s performance, you can rollback or adjust. You might use simple version comments or maintain the instructions text in a version-controlled repository (especially for complex custom agents).

In summary, don’t treat instruction-writing as a one-off task. Embrace user feedback and analytic insights to continually hone your agent. Many successful Copilot agents likely went through numerous instruction revisions. Each iteration brings the agent’s behavior closer to the ideal.

Tailoring Instructions to Different Agent Types and Scenarios

No one-size-fits-all set of instructions will work for every agent – the content and style of the instructions should be tailored to the type of agent you’re building and the scenario it operates in[3]. Consider the following variations and how instructions might differ:

- Conversational Q\&A Agents: These are agents that engage in a back-and-forth chat with users (for example, a helpdesk chatbot or a personal finance Q\&A assistant). Instructions for conversational agents should prioritize dialog flow, context handling, and user interaction. They often include guidance like how to greet the user, how to ask clarifying questions one at a time, how to not overwhelm the user with too much info at once, and how to confirm if the user’s need was met. The example instructions we discussed (IT support agent, ShowExpert recommendation agent) fall in this category – note how they included steps for asking questions and confirming understanding[4][1]. Also, conversational agents might need instructions on maintaining context over multiple turns (e.g. “remember the user’s last answer about their preference when formulating the next suggestion”).

- Task/Action (Trigger) Agents: Some Copilot Studio agents aren’t chatting with a user in natural dialogue, but instead get triggered by an event or command and then perform a series of actions silently or output a result. For instance, an agent that, when triggered, gathers data from various sources and emails a report. Instructions for these agents may be more like a script of what to do: step 1 do X, step 2 do Y, etc., with less emphasis on language tone and conversation, and more on correct execution. You’d focus on instructions that detail workflow logic and error handling, since user interaction is minimal. However, you might still include some instruction about how to format the final output or what to log.

- Declarative vs Custom Agents: In Copilot Studio, Declarative agents use mostly natural language instructions to declare their behavior (with the platform handling orchestration), whereas Custom agents might involve more developer-defined logic or even code. Declarative agent instructions might be more verbose and rich in language (since the model is reading them to drive logic), whereas a custom agent might offload some logic to code and use instructions mainly for higher-level guidance. That said, in both cases the principles of clarity and completeness apply. Declarative agents, in particular, benefit from well-structured instructions since they heavily rely on them for generative reasoning[7].

- Different Domains Require Different Details: An agent’s domain will dictate what must be included in instructions. For example, a medical information agent should have instructions emphasizing accuracy, sourcing from medical guidelines, and perhaps disclaimers (and definitely instructions not to venture outside provided medical content)[1][1]. A customer service agent might need a friendly empathetic tone and instructions to always ask if the user is satisfied at the end. A coding assistant agent might have instructions to format answers in code blocks and not to provide theoretical info not found in the documentation provided. Always infuse domain-specific best practices into the instruction. If unsure, consult with subject matter experts about what an agent in that domain must or must not do.

In essence, know your agent’s context and tailor the instructions accordingly. Copilot Studio’s own documentation notes that “How best to write your instructions depends on the type of agent and your goals for the agent.”[3]. An easy way to approach this is to imagine a user interacting with your agent and consider what that agent needs to excel in that scenario – then ensure those points are in the instructions.

Resources and Tools for Improving Agent Instructions

Writing effective AI agent instructions is a skill you can develop by learning from others and using available tools. Here are some resources and aids:

- Official Microsoft Documentation: Microsoft Learn has extensive materials on Copilot Studio and writing instructions. Key articles include “Write agent instructions”[3], “Write effective instructions for declarative agents”[4], and “Optimize prompts with custom instructions”[6]. These provide best practices (many cited in this report) straight from the source. They often include examples, do’s and don’ts, and are updated as the platform evolves. Make it a point to read these guides; they reinforce many of the principles we’ve discussed.

- Copilot Prompt Gallery/Library: There are community-driven repositories of prompt examples. In the Copilot community, a “Prompt Library” has been referenced[7] which contains sample agent prompts. Browsing such examples can inspire how to structure your instructions. Microsoft’s Copilot Developer Camp content (like the one for ShowExpert we cited) is an excellent, practical walkthrough of iteratively improving instructions[7][7]. Following those labs can give you hands-on practice.

- GitHub Best Practice Repos: The community has also created best practice guides, such as the Agents Best Practices repo[1]. This provides a comprehensive guide with examples of good instructions for various scenarios (IT support, HR policy, etc.)[1][1]. Seeing multiple examples of “sample agent instructions” can help you discern patterns of effective prompts.

- Peer and Expert Reviews: If possible, get a colleague to review your instructions. A fresh pair of eyes can spot ambiguities or potential misunderstandings you overlooked. Within a large organization, you might even form a small “prompt review board” when developing important agents – to ensure instructions align with business needs and are clearly written. There are also growing online forums (such as the Microsoft Tech Community for Power Platform/Copilot) where you could ask for advice (without sharing sensitive details).

- AI Prompt Engineering Tools: Some tools can simulate how an LLM might parse your instructions. For example, prompt analysis tools (often used in general AI prompt engineering) can highlight which words are influencing the model. While not specific to Copilot Studio, experimenting with your instruction text in something like the Azure OpenAI Playground with the same model (if known) can give insight. Keep in mind Copilot Studio has its own orchestration (like combining with user query and tool descriptions), so results outside may not exactly match – but it’s a way to sanity-check if any wording is confusing.

- Testing Harness: Use the Copilot Studio test chat repeatedly as a tool. Try intentionally weird inputs to see how your agent handles them. If your agent is a Teams bot, you might sideload it in Teams and test the user experience there as well. Treat the test framework as a tool to refine your prompt – it’s essentially a rapid feedback loop.

- Telemetry and Analytics: Post-deployment, the telemetry (if available) is a tool. Some enterprises integrate Copilot agent interactions with Application Insights or other monitoring. Those logs can reveal how the agent is being used and where it falls short, guiding you to adjust instructions.

- Keep Example Collections: Over time, accumulate a personal collection of instruction snippets that worked well. You can often reuse patterns (for example, the generic structure of “Your responsibilities include: X, Y, Z” or a nicely phrased workflow step). Microsoft’s examples (like those in this text and docs) are a great starting point.

By leveraging these resources and tools, you can improve not only a given agent’s instructions but your overall skill in writing effective AI instructions.

Staying Updated with Best Practices

The field of generative AI and platforms like Copilot Studio is rapidly evolving. New features, models, or techniques can emerge that change how we should write instructions. It’s important to stay updated on best practices:

- Follow Official Updates: Keep an eye on the official Microsoft Copilot Studio documentation site and blog announcements. Microsoft often publishes new guidelines or examples as they learn from real-world usage. The documentation pages we referenced have dates (e.g., updated June 2025) – revisiting them periodically can inform you of new tips (for instance, newer versions might have refined advice on formatting or new capabilities you can instruct the agent to use).

- Community and Forums: Join communities of makers who are building Copilot agents. Microsoft’s Power Platform community forums, LinkedIn groups, or even Twitter (following hashtags like #CopilotStudio) can surface discussions where people share experiences. The Practical 365 blog[2] and the Power Platform Learners YouTube series are examples of community-driven content that can provide insights and updates. Engaging in these communities allows you to ask questions and learn from others’ mistakes and successes.

- Continuous Learning: Microsoft sometimes offers training modules or events (like hackathons, the Powerful Devs series, etc.) around Copilot Studio. Participating in these can expose you to the latest features. For instance, if Microsoft releases a new type of “skill” that agents can use, there might be new instruction patterns associated with that – you’d want to incorporate those.

- Experimentation: Finally, don’t hesitate to experiment on your own. Create small test agents to try out new instruction techniques or to see how a particular phrasing affects outcome. The more you play with the system, the more intuitive writing good instructions will become. Keep notes of what you learn and share it where appropriate so others can benefit (and also validate your findings).

By staying informed and agile, you ensure that your agents continue to perform well as the underlying technology or user expectations change over time.

Conclusion: Writing the instructions field for a Copilot Studio agent is a critical task that requires careful thought and iteration. The instructions are effectively the “source code” of your AI agent’s behavior. When done right, they enable the agent to use its tools and knowledge effectively, interact with users appropriately, and achieve the intended outcomes. We’ve examined how good instructions are constructed (clear role, rules, steps, examples) and why bad instructions fail. We established best practices and a T-C-R framework to approach writing instructions systematically. We also emphasized testing and continuous refinement – because even with guidelines, every use case may need fine-tuning. By avoiding common pitfalls and leveraging available resources and feedback loops, you can craft instructions that make your Copilot agent a reliable and powerful assistant. In sum, getting the instructions field correct is crucial because it is the single most important factor in whether your Copilot Studio agent operates as designed or not. With the insights and methods outlined here, you’re well-equipped to write instructions that set your agent up for success. Good luck with your Copilot agent, and happy prompting!

References

[1] GitHub – luishdemetrio/agentsbestpractices

[2] A Microsoft 365 Administrator’s Beginner’s Guide to Copilot Studio

[3] Write agent instructions – Microsoft Copilot Studio

[4] Write effective instructions for declarative agents

[5] From Scribbles to Spells: Perfecting Instructions in Copilot Studio

[6] Optimize prompts with custom instructions – Microsoft Copilot Studio

[7] Level 1 – Simple agent instructions – Copilot Developer Camp