This article is a part of a series. The previous article can be found here:

All the Guards – Part 5 (Credential Guard)

In this article I’m going to focus on the next component, which is:

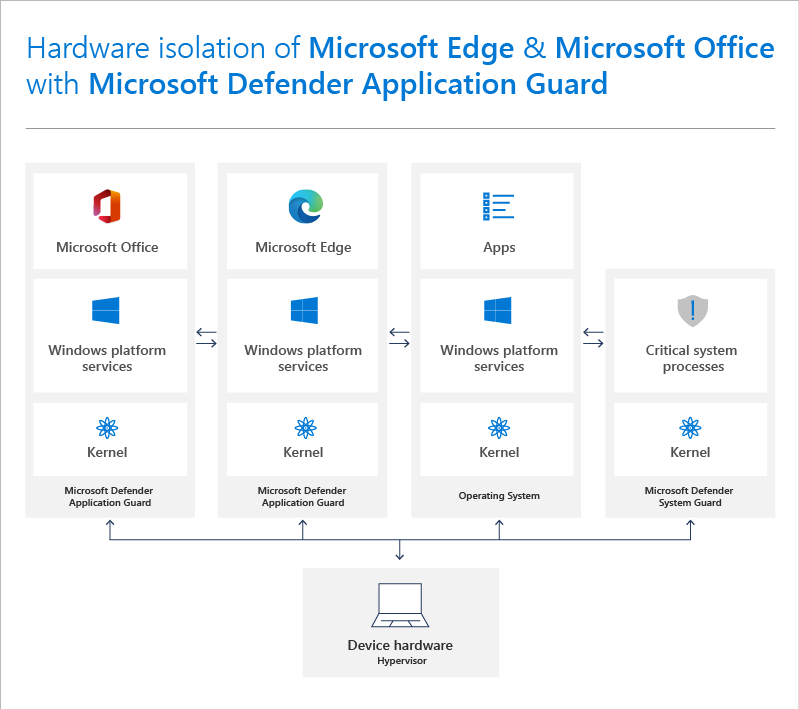

For Microsoft Edge, Application Guard helps to isolate enterprise-defined untrusted sites, protecting your company while your employees browse the Internet. As an enterprise administrator, you define what is among trusted web sites, cloud resources, and internal networks. Everything not on your list is considered untrusted. If an employee goes to an untrusted site through either Microsoft Edge or Internet Explorer, Microsoft Edge opens the site in an isolated Hyper-V-enabled container.

For Microsoft Office, Application Guard helps prevents untrusted Word, PowerPoint and Excel files from accessing trusted resources. Application Guard opens untrusted files in an isolated Hyper-V-enabled container. The isolated Hyper-V container is separate from the host operating system. This container isolation means that if the untrusted site or file turns out to be malicious, the host device is protected, and the attacker can’t get to your enterprise data. For example, this approach makes the isolated container anonymous, so an attacker can’t get to your employee’s enterprise credentials.

In essence, Application Guard provides an sandbox to use with your browser and Office. Untrusted web sites and documents are open in this sandbox to provide isolation from the rest of the system for security. You can implement Application Guard on both Windows 10 Pro and Enterprise out of the box as well as with Edge and other common browsers.

You can read about the specific:

System Requirements for Microsoft Defender Application Guard

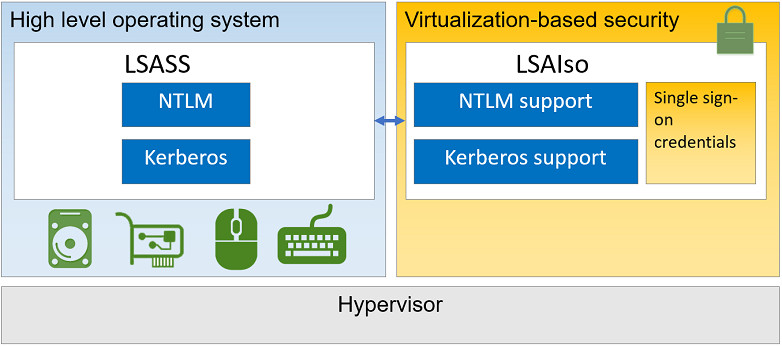

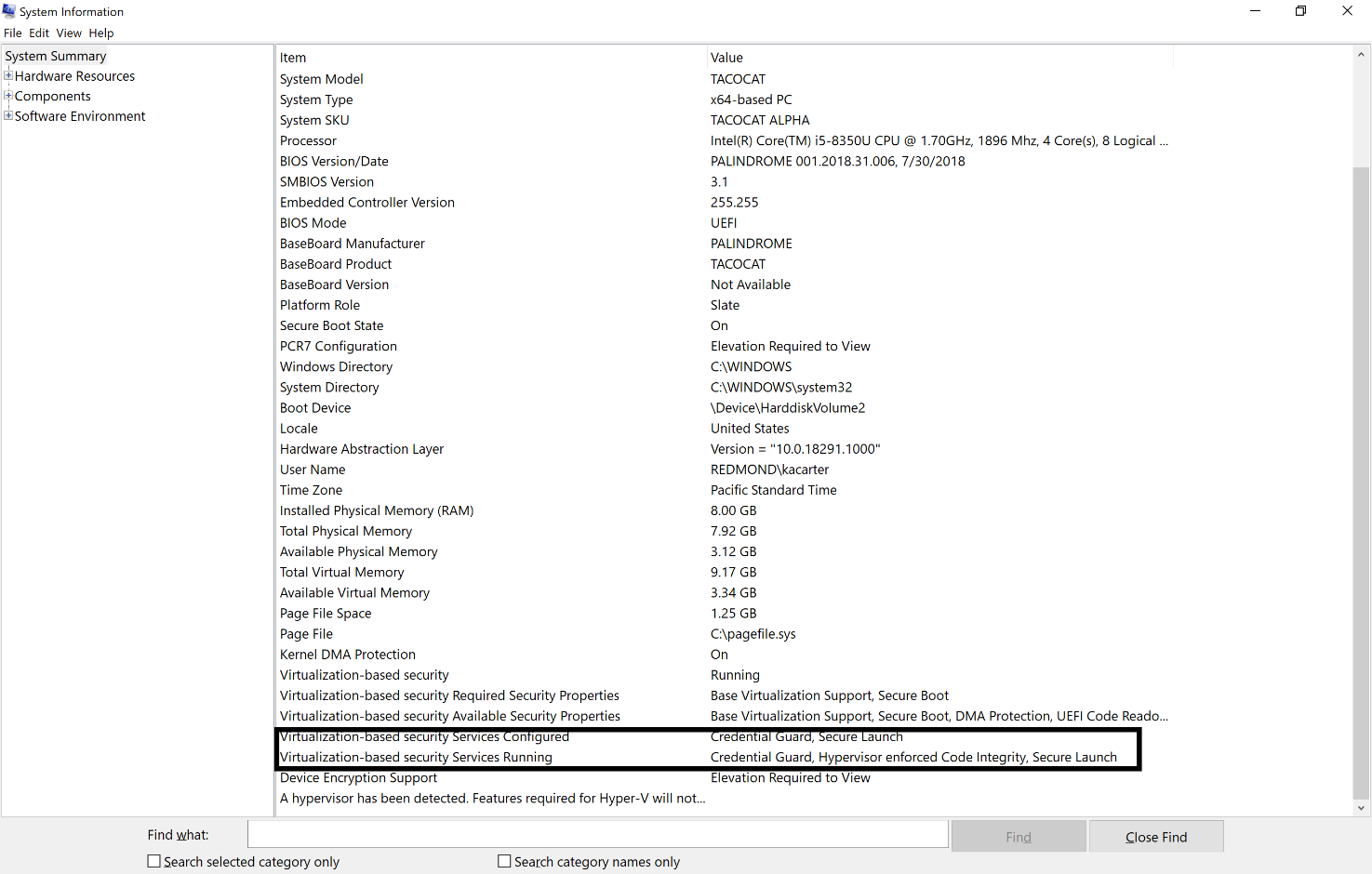

but in essence you’ll need the

Virtualization Based Security (VBS)

configured prior.

There are various ways to enable Application Guard and you’ll find these here:

Prepare to install Microsoft Defender Application Guard

However, the easiest way is to enable Application Guard is by adding the Microsoft Defender Application Guard feature to Windows from the Control Panel as shown above.

If you are an administrator then you will also want to take a look at:

Remember there is Application Guard for Edge and for Office:

However, to use the Office version you’ll currently need Microsoft 365 E5.

Getting Application Guard to work as expected can be a tricky endeavour because it relies on things like Network Boundaries to define trusted and untrusted sites, which are determined by policy configurations. For all this, I suggest you take a look at my earlier article:

Getting Windows Defender Application Guard (WDAG) working

That article will also show you how to use the:

Windows Defender Application Guard Companion

which is really handy if you want to run Application Guard manually, which you’ll typically have to do unless you are using Windows 10 Enterprise.

Another handy resource is:

Frequently asked questions – Microsoft Defender Application Guard

To test your environment see:

Application Guard testing scenarios

Finally, here is a nice overall summary guide:

Windows 10 – All things about Application Guard

which importantly, provides the following troubleshooting tips:

- To reset (clean up) a container and clear persistent data inside the container:

- 1. Open a command-line program and navigate to Windows/System32.

2. Type wdagtool.exe cleanup. The container environment is reset, retaining only the employee-generated data.

3. Type wdagtool.exe cleanup RESET_PERSISTENCE_LAYER. The container environment is reset, including discarding all employee-generated data.

Window Defender Application Guard is a great way to provide a sandbox for your browser as well as Office documents. The main limitation is that many of the automated features are only available if you are using Windows 10 Enterprise but that doesn’t stop you adopting Application Guard for your environment I would suggest, as any impact can easily be minimised for Windows 10 Pro environments.

Next up will be:

.png)